»In South Africa you don't decide to join politics;

politics decides to join you.«

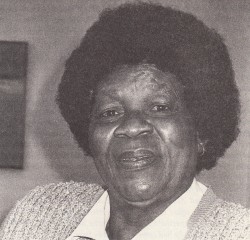

RUTH MOMPATI

It would be impossible to include in this section all the major anti-apartheid organizations or movements in South Africa. Before the United Democratic Front was banned in February 1988, it was an umbrella organization for over eight hundred different anti-apartheid groups with a combined membership of over two million people. Of the many other anti-apartheid organizations that did not choose to unite under the UDF rubric, one of the most important is the Azanian People's Organization. In addition, there are banned organizations that have to operate underground. Although part II is thus necessarily incomplete,[1] the accounts of the six women included here, as well as those of other women in this volume, demonstrate some of the diversity in the anti-apartheid organizations, past and present, that make up the South African liberation struggle.

The African National Congress is by far the most powerful and the most popular of the many anti-apartheid organizations. Founded in 1912, the ANC was banned in 1960 along with the Pan-Africanist Congress, which had split off from it in 1959 because of the ANC's willingness to work with whites and communists. The ban is still in effect today. Consequently, no one in South Africa can openly admit to membership in these organizations.

Although I interviewed some women in South Africa who talked about their participation in the ANC before it was banned, I spoke to no one who admitted current involvement in the ANC underground. Indeed, I did not ask women whether they were thus engaged, or seek out such women, lest I endanger them. In order to get an up-to-date view of the ANC, I interviewed women at the ANC headquarters in Lusaka, Zambia.

I was ushered into the ANC Women's Section[2] office, where I sat in a circle with eight of the women who worked there. They asked me to explain my project, its goals, who I am, and who I had seen in South Africa. Although I was aware that I had to win their approval, they were friendly and intensely interested in news from their homeland. I was struck by the modesty of their office facilities and the ANC headquarters in general. Clearly, the funds donated to them are not spent on fancy desks and wall-to-wall carpets.

After about an hour of questions, the women made it clear that they wanted to assist my project; now the problem became how to keep the number of interviews manageable. I was pleased with their choices, but space permits the inclusion here of only three of the five women I interviewed: Ruth Mompati, the most senior woman in the ANC power structure; Mavivi Manzini, secretary for publicity, information, and research for the Women's Section; and Connie Mofokeng, who in chapter 2 describes her escape from a South African prison after being severely tortured. All five women came to my hotel room to be interviewed at prearranged times over a two-day period. While this arrangement was convenient, it deprived me of the opportunity to see the women in their usual work or home settings.

Chapters 9, 10, and 11 are presented in order of historical occurrence. First, Ela Ramgobin describes the famous Defiance Campaign, launched by the ANC and the South African Indian Congress in 1952, in which thousands of people participated in civil disobedience. She also gives an account of the revival of the Natal Indian Congress in the early 1970s, and the important role it played in bringing to life again the longdormant anti-apartheid movement.

Although Albertina Sisulu's political work predates by many years the formation of the United Democratic Front in 1983, I have included her here in her role as co-president of UDF. As already mentioned, this organization has undoubtedly been the most significant legal anti-apartheid organization in South Africa in recent years. Although most UDF members and leaders have been black, a few whites have also been active participants. Because the UDF chose for its patrons all the long-term ANC prisoners, many people have seen it as a child of the ANC. What will happen now that it, too, has been banned, I cannot say.

In chapter 11, Paula Hathorn, chairperson of the End Conscription Campaign in Cape Town, describes the philosophy and actions of this important white anti-apartheid organization since it was launched in 1983. Despite ECC's commitment to work within the limitations of the increasingly repressive South African laws, this organization was also banned in August 1988.

This part begins with Winnie Mandela, one of the most famous people in South Africa, and without a doubt, the best-known woman there.

A Leader in Her Own Right

»The years of imprisonment hardened me... Perhaps if you

have been given a moment to hold back and wait for the

next blow, your emotions wouldn't be blunted as they have

been in my case. When it happens every day of your life,

when that pain becomes a way of life,

I no longer have the emotion of fear.«

WINNIE MANDELA

Although her fame used to be due in large part to her marriage to Nelson Mandela, the most revered and popular leader of the South African liberation movement, Winnie Mandela is a powerful personality and leader in her own right, with an extraordinarily strong and regal presence. It was all the more painful, then, to read the news, which made world headlines in late December 1988 and the first months of 1989, alleging that she had participated in the beating of four young and-apartheid activists. (One of these victims, fourteen-year-old Stompie Moeketsi, was later found dead, allegedly killed by members of the Mandela United Football Club, who served as her bodyguards.) If there is any truth in these ugly accusations against Winnie Mandela, made by Stompie's three companions and some of the leaders of the United Democratic Front, it is important to remember what we have learned from the literature on torture and concentration camps—including the torture of battered women: that every human being has a breaking point. It is clear from Winnie's interview here that she has been subjected to decades of intense persecution by the government and its agents—the security police —and has suffered long years of separation from her husband and children. Her present situation may well be a tragic consequence of this persecution and of the great isolation that, as a black woman and famous anti-apartheid leader in an extremely racist and sexist society, she has had to endure. The possible role of infiltrators and provocateurs among her football players-cum-bodyguards (a common weapon of the South African government against the anti-apartheid movement) may also turn out to have played a pivotal role.

While we may never know the full story, nothing can take away from the tremendous courage and spirit that Winnie Mandela has shown in the face of painful and often devastating experiences that would have broken ordinary people years ago.

Born Nomzamo Winifred Madikizela in 1934, Winnie Mandela (as she is usually called) is an African and mother of two daughters, Zeni and Zindzi. Mandela, passionately committed to the struggle, has been in and out of prison so many times that she cannot keep track of the dates.

In the following interview, Mandela gives a poignant description of her childhood years in a rural area of Pondoland, now part of the Transkei. One of the poorest parts of the country today, the Transkei became the first of the so-called homelands for Africans—specifically for Xhosas—in 1976. Despite the opposition of many Xhosa people, Chief Kaiser Matanzima, the traditional leader of the Transkei, accepted the white government's offer of a kind of nominal independence. But this manifestation of apartheid occurred after the sixteen-year-old Mandela had left the area for Johannesburg, where she still lives in the large black township of Soweto.

We learn about the infamous treason trial in which 156 leaders of the congress movement, the major coalition of anti-apartheid organizations during the period when it occurred (1956-61), were charged with high treason. Among them was her future husband, Nelson Mandela, whom she first met when he called her up to ask her to raise funds for this trial. Sixteen years her senior, Nelson was—in 1956— already one of the most outstanding of an impressive group of African National Congress leaders. After a grueling five years, all 156 of those charged with treason were acquitted, much to the chagrin of the South African government.

Three months after Winnie Mandela married Nelson in 1958, she was arrested for participating in the historic anti-pass campaign organized by women in an effort to prevent the hated passes—an identity document men had been forced to carry for decades—from being extended to women. (The African women's militant and effective campaign against passes, as early as 1913, was one reason they did not have to carry passes sooner.) This arrest was just the first of many for Mandela, who remained under banning orders continuously from 1961 to 1975.[3]

In 1969, Mandela was detained under section 6 of the Terrorism Act, without having been found guilty in a court of law. She was held in solitary confinement for seventeen months, an experience she describes in the following pages. She was finally released in 1970 after having been acquitted twice. Her relief was short-lived, since she was immediately banned and house-arrested on leaving prison. She was subsequently charged many times for breaking her banning orders.

One of these contraventions resulted in another six-month jail sentence in 1974.

Since nothing seemed to stop Mandela from continuing with her political work (for example, helping to found the Black Women's Federation in 1975 and the Black Parents' Association in Soweto in 1976), the government finally banished her in 1977 to Brandfort, a small, conservative, Afrikaner dorp [town] in the Orange Free State. Mandela explains in her interview why she found living in Brandfort for eight years one of the most painful times in her life. After her home there was fire-bombed in 1985, she defied her banishment order and returned to her Soweto home amidst a great national and international furor. Her determination and courage paid off, and she was finally allowed to stay in Soweto.

In earlier years, Mandela had been active with the Women's League of the African National Congress and with the Federation of South African Women (described by Helen Joseph in some detail in chapter 15). Despite her leadership role in the anti-apartheid movement, Mandela explained to me: »I have really been more engaged in the struggle at the grassroots level. Partly because of my training as a social worker, I have always considered myself as belonging there. I prefer to work with ordinary people and to be part of them. If I had had a choice, I would never have wanted to be in the limelight«.

Despite the extremity of the persecution to which Mandela has been subjected, she does not hesitate to say that she is willing to suffer more. The depth of the religious feeling and commitment evident in her interview is in sharp contrast to the South African government's portrayal of the African National Congress (with which she is identified) as a godless, communist organization.

Of the sixty interviews I conducted, the one with Mandela was by far the most difficult to arrange. It involved a visit to Mandela's lawyer, Ismail Ayob; a visit to Soweto to hand-deliver a lengthy handwritten plea to Mandela to consent to an interview, more than fifteen phone calls; one inexplicable failure to connect with each other at a prearranged meeting place; a postponement of my flight out of the country; and a mysterious tape-recorder failure when I finally started the long-awaited interview at Mandela's home in Soweto. Her response to the last of these calamities was one of total equanimity. »I'm used to sabotage«, she commented, as she went out of the room, leaving me in a state of suppressed hysteria and shock. Fortunately my frantic random fiddling somehow got the treacherous machine to work again, and I was able to proceed with the interview.

Growing Up African

I come from a remote country village in the Transkei, one of nine children. I grew up in the countryside looking after cattle and sheep. It was a wonderful childhood in a way, although I felt the pains of apartheid from an early time. But the environment was very healthy. We were not in an urban situation where you are confronted with apartheid every day of your life. As a child I used to wake up at three in the morning to go to the fields to hoe and look after the crops. I would come home with the other girls who lived in the area, wash up, and then go to school. At times we used to alternate between going to school and working in the fields. We knew that if there was no harvest from the mealie [maize] fields we were going to have worse times. Our livelihood depended on it.

We learned from the white local traders and their families that there were people of another color and standard of living. We knew from a very early age that our parents were peasants and that, in order to maintain us, they were dependent on a white man who looked down on us. We found ourselves in a derogatory kind of environment with supercilious white children, our counterparts, who wore better-quality clothes than we did.

I wore shoes for the first time when I passed my standard six [eighth grade] and went to boarding school. I was just beginning puberty, which was a difficult age for a deprived child. I wanted to look like other little girls. I was beginning to be conscious of who I was, and wanted to have so much, but there wasn't any money. I came from a very large family. There were eleven of us, and I came right in the middle, so my birth was of no particular consequence. I was a very difficult child—extremely naughty—and, because there were fewer boys in the family, I tended to regard myself as a boy. I was a terrible tomboy, the truth of which is borne out by the fact that my body is full of horrible scars. I used to fall from trees and that sort of thing, but I wouldn't report these mishaps to my mother. According to the adults, I gave my mother a lot of trouble.

My parents were on the fanatical side. My mother was an extremely devoted Christian who taught me to respect adults, and part and parcel of that was to respect the missionaries who were invariably white. We literally had to revere the white missionary because he commanded so much authority, and in a rural setup, he was one whose advice everybody sought. These were Methodist missionaries, and we attended Methodist missionary schools. So we grew up becoming subservient to men of another color, whether they were missionaries or local traders. But then one day, when I was in standard three or four, I suddenly asked »But why? This is my country«

My father was our teacher, and he taught us the history of our country. »This is what you are going to find in the text«, he would say. »This is how the white man wrote your history. But I am telling you that, contrary to what this white man says, it is so and so. These books were written to condition you into believing that the whites are your masters« I learned this for the first time from my own father.

And my grandmother, his mother, was an extraordinary woman who exercised a great deal of influence on all of us. She was a tough, robust woman with the physique of a fighter. She was the woman who taught me the power and strength of a woman, and that the real head of the family is a woman. My grandfather was a chief (my father refused to take up chiefdomship) and my grandmother was one of twenty-nine wives and was widowed very early in her life. She was the first woman in that part of our country to have owned a small trading post, by virtue of being a senior wife to the chief. My grandfather is reported to have worked hand in hand with the local traders. Because he had given them a large piece of land, they thanked him by giving him a little trading post, which was run by my grandmother. She must have resented whites very deeply because when the particular whites she had dealt with left, the subsequent local traders took this small trading post from her. She was extremely bitter about this. She taught us that these people of the other color are thieves. All they are here for is to steal our land and our cattle. With what my grandmother instilled in us at home and my father taught us in school, I realized I was growing up in a blistering inferno of racial hatred which was, of course, emphasized by the Afrikaner when he took over the government in 1948.

Some of my uncles worked in the gold mines, so I learned about migratory labor in my childhood. I was very fond of these uncles who would disappear for months. I saw their young wives toiling. They would come to my mother who was a senior wife, and I would listen to them crying and telling her tales about their hardships: how difficult it was for them to bring up children; how they were no longer hearing from their husbands. I began questioning why the children would be deprived of their parents for so many months when the local traders and the local priest never left their children. We witnessed this agony and learned of the horrors of migratory labor in a physical sort of way, so when I talk about these things on the platform, my heart bleeds from many generations of pain.

Political Activity

I first heard of the names of Mandela and Tambo in 1953 when I was doing my matric. There was a Defiance Campaign in Johannesburg at that time, and I heard that these leaders had told the country to defy unjust laws. The level of consciousness at our country high school was already far advanced at that time, and our interpretation of that instruction was that we must defy school authority. We didn't even write exams that year because we went on strike because of insufficient food and complaints about the general administration of the school. As long ago as that, the name of the African National Congress was instilled in our minds. Immediately after I graduated, I lived in a girls' hostel in Johannesburg. There were political discussions at the hostel almost daily, and it was there that I came across the names of Mandela and Tambo.

I was the first black medical social worker in the country. I worked at the Baragwanath Hospital, specializing in pediatric social work. It was one of the most painful fields to work in because I came into physical contact with the infant mortality rate and the gross malnutrition my people were suffering. I witnessed the pains of bringing up children without any means. I was aware of the desperation of my people trying to make ends meet in a society which was entirely capable of looking after all of its inhabitants. I began to question the role of social workers and felt that we were not being effective at all. I saw us as nothing more than civil servants. All I did was to refer cases to white institutions because there were no facilities for black people. We had no orphanages, we had no homes for disabled children, we had no homes for cerebral palsy cases. It was then that I really became conscious of the fact that if one was to be counted as a human being of fiber, one has to play a role in changing society. So I only worked as a medical social worker for three years.

I was doing social work at Baragwanath when I was telephoned by Nelson Mandela who wanted me to assist him with raising funds for the 1957 treason trial. Although Mandela [4] was a patron of the Ann Hofmeyr School of Social Work where I had trained, I had never met him before. But I used to read about him like all the other girls. When he called me up and asked me to help raise funds, I agreed because I wanted to be more involved in the liberation of my people. From that moment on, I attended the treason trial regularly and came into direct contact with the leaders of the people for the first time. Then in 1958 we married.

Attending the treason trial was for me the greatest thing to happen in my life. I was able to meet for the first time great Christians and great leaders like Chief Albert Luthuli [a former president of the ANC and Nobel Peace Prize winner]. I met Oliver Tambo, Duma Nokwe, Moses Kotane, and Walter Sisulu [well-known ANC leaders]. And my greatest experience was meeting a woman who was my hero at that time, Lillian Ngoyi [a former president of the Federation of South African Women]. We all worshiped her. Her name was a legend in every household, and we all aspired to be a Lillian Ngoyi when we grew up. When I actually met her, I found out how down to earth this great woman was. I subsequently attended meetings because I wanted to hear her and experience the power she had to grip the country. She was one of the greatest orators I have ever heard, one of the greatest women I have lived to know. And you could feel she was self-taught. I felt some kind of physical identity with her because she belonged to the working class. She spoke the language of the worker, and she was herself an ordinary factory worker. When she said what she stood for, she evoked emotions no other person could evoke. She was a tremendous source of inspiration. She spoke on behalf of the Women's League of the African National Congress and the Federation of South African Women, of which she was the president at that time. She worked closely with Mama [5] Helen Joseph [a leader in the now-defunct Federation of South African Women; see chapter 15] and various other great women like the late Florence Matomela and Frances Baard [former leaders of the ANC Women's League and the Federation of South African Women], whom we also worshiped very dearly.

And then there were my immediate seniors like Albertina Sisulu [see chapter 10], a woman who was a tremendous source of inspiration and who gave me a lot of courage when Mandela went underground. I went to her when times were very hard and it was very difficult to pull through. I had been jailed with her in 1958, which was my very first experience in prison.

[Before the Soweto uprising,] I was very involved in organizing the people and conscientizing [a South African word for »consciousness raising"] them about the extremely dangerous situation that was developing. Walking in the streets of Soweto in 1976, you could feel that we were heading toward a climax between the security forces and the oppressed people of this country. I met with a few leaders here and suggested that we form the Black Parents' Association to encompass the entire country, because it was obvious then that the outbreak of anger against the state wasn't necessarily going to be confined to Soweto. The government regarded me as having played a major role in the formation of these organizations and in generally encouraging the students' militancy toward the state. Although it would be wonderful to imagine that I have such organizational powers, it was madness to think I was responsible for these things. This was a spontaneous reaction to the racial situation in the country—an explosion against apartheid.

I don't think I will ever erase the memory of those days from my subconscious mind. It was the most painful thing to witness—the killing of our children, the flow of blood, the anger of the people against the government, and the force that was used by the government on defenseless and unarmed children. I was present when it started. The children were congregated at the school just two blocks away from here. I saw it all. There wasn't a single policeman in sight at that time, but they were called to the scene. When they fired live ammunition on the schoolchildren, when Hector Petersen, a twelve-year-old child, was ripped to pieces, his bowels dangling in the air, with his little thirteen-year-old sister screaming and trying to gather the remains of her brother's body, not a single child had picked up even a piece of soil to fling at the police. The police shot indiscriminately, killing well over a thousand children.

Prison, Banning, Banishment

I was one of over six hundred women arrested in the anti-pass campaign of 1958. We were trying to stop the extension of the pass laws to women. These laws had already caused tremendous damage to black people by causing the disintegration of black family life. Black men had been carrying the hated pass for years—a document that was calculated not only to prevent the influx of blacks into the urban areas, but also to dehumanize those of a darker skin and to make them feel nonpersons and sojourners in urban, white, racist South Africa. We had completely lost the concept of the family as the nucleus of our community. Men were imprisoned endlessly. The laws declared them automatic criminals by virtue of their color.

Because of the physical brutality of prison life, I nearly lost my eldest child, who I was three months pregnant with at the time. I was fortunate to be there with Albertina [Sisulu], who is a nurse. Most of us were in prison for six weeks on this occasion, but the movement decided that Albertina and all the nursing sisters were needed during the crisis, so they had to leave prison. Although she only stayed there for a few days, she helped me a great deal.

I have spent most of my life in and out of prison. I can't remember how many times I have been inside, and it isn't possible to give dates. At first I was bewildered like every woman who has had to leave her little children clinging to her skirt and pleading with her not to leave them. I cannot, to this day, describe that constricting pain in my throat as I turned my back on my little ghetto home, leaving the sounds of those screaming children as I was taken off to prison. As the years went on, that pain was transformed into a kind of bitterness that I cannot put into words.

Solitary confinement was frightening at first because my thoughts were with my children all the time. Their father, whom they had never known, was in prison. They had never known the pleasure of having a family, of having a father figure, and there I was in prison without having had the opportunity to make arrangements for them. I didn't even know where they were, nor what had happened to them that night. That was the only thing that frightened me. What was going to happen to my children? What would become of them? What if I was held for ten years? What if whatever they would cook up as evidence against me, stuck, and I was sentenced to many years of imprisonment? How was I going to bring up my young children from prison? Those were my only fears. The police made me believe that I would be in prison forever — that I had reached the road to the end of eternity. Even experienced politicians come to believe this kind of threat because of the psychological warfare that is conducted.

It was my nine years in exile in Brandfort that was the worst experience of my life. They banished me there because they believed I was in the forefront of the 1976 Soweto uprising. The government imagines it can solve the country's problems by uprooting human beings and exiling them to deserts. Those years have brutalized me more than all the times I was in prison. My experience there was calculated to leave my soul in shreds: to so dehumanize me that nothing would be left in me to fight with; to tear apart my spirit so that life wouldn't be worth living.

I was flung into a crude, dirty, three-roomed building in Brandfort, which was without water or electricity and which was full of soil. They brought prisoners to scoop up the soil, and they threw water on the floor and walls to settle the dust. Zindzi [her youngest daughter] and I spent the first night sitting on bundles of our clothes because there was nowhere to sleep. They had taken everything I had possessed with pride, Mandela's last possessions, little things that make one what one is. They threw them onto bedspreads and sheets—whether it was cutlery or breakable plates or my house ornaments—and tied them into bundles. That is how everything was conveyed to Brandfort, and most of the things were broken in the process.

Zeni was sixteen and a half and living in Swaziland when I was banished. Zindzi was fifteen and on vacation from school. Banishing me meant banishing her as well. To do that to a little girl that age in her developing years is unforgivable. That kind of scar never heals. One of the most painful things for me was seeing that child in exile with me.

I refused to stay in Brandfort. I wanted to set a precedent that unjust laws are meant to be defied, and that I could no longer continue obeying an immoral government. Half of my life I have spent complying with their regulations to satisfy their sadism. It has become a personal vendetta by the state against me. I came back to Johannesburg not only because I was imprisoned in that ghetto home in Brandfort for nine years, but because they finally destroyed the very ghetto home they had exiled me to by firebombing everything I possessed. Everything I had went up in flames forcing me to start from scratch again.

The government has kept harassing me and treating me like a common criminal. I asked myself what it meant for them to be so scared— despite the fact that I hadn't any power to do anything in retaliation for what they were doing to me. Does it mean that what I stand for is so true that it is like the story of Jesus Christ? Is that story of the Bible the real story of life? That for one to attain one's aspirations, one has to pass through this road of crucifixion?

The years of imprisonment hardened me. I no longer felt their powers of harassment. Later I was transformed from that bitterness into the realization that those who are fighting like me, and the cause we are fighting for, must be worth a great deal; and that if this is the path through which I have to tread in order to reach that goal, then God has designed it that way. It is God's wish that those He handpicks to tread on this path must reach that Golgotha, because that is then the end of that journey to liberation. Perhaps I am one of the chosen ones, and therefore God gives me the strength and the energy to carry on, no matter how bitter the struggle. And if He wishes that my blood, as in the case of Jesus Christ, be spilt for this purpose—then, God, let it be. Because He made us, He alone determines our path, He knows whom He has chosen for which task.

Marriage and Children

I've never had the opportunity to live with Mandela. When we got married in 1958, he was being tried for treason, and he lived in Pretoria where the trial took place. And when the treason trial came to an end, he went to address a convention in Pietermaritzburg. We were together when he had time to come home for weekends, but those times wouldn't add up to even six months. So I have never really known what married life is. I have always known him as a prisoner. I feel deeply wounded about this and very angry that human beings can be kept apart for a lifetime, not because they committed any capital offense, but because they simply disagree with another man's ideas. But I'm convinced that Mandela will be released because of the pressure of the international community, the internal pressure from the oppressed people themselves, and the deterioration in the political situation in this country.

The historical period in which our children, Zindzi and Zeni, live has made their experiences no different from the ordinary black child in the street. It is a life of deprivation, a life in a sick society that deprives families of what belongs to them; that even deprives families of the duty of parenting their own children. My daughter Zindzi was detained for three weeks about three years ago. Zeni hasn't been detained only because she is a Swazi national and carries a Swazi diplomatic passport because she is married to a young prince in Swaziland.

I have had to live with a permanent threat to my life, a permanent threat to my family, and a permanent threat to almost my entire extended family. This includes my brothers and sisters who are not political at all. One of my sisters died in exile in Botswana, not because she was political herself, but because I was closest to her. She had to leave this country and live as an expatriate in Botswana.

I can no longer say what many of my colleagues find themselves having to say at one stage or another: »Off the record, I can tell you this is so and so, but I can't say it publicly because I have a family to feed. If I am known to expound such views, I'll be jailed« In my case there is no longer anything I can fear. There is nothing the government has not done to me. There isn't any pain I haven't known.

The Most Powerful Woman

in the African National Congress

»As a woman, not only do you have to be good, but you've got

to be better than the men. This is the load that women

have to carry.

You can't afford to make the slightest mistake«

RUTH MOMPATI

...has the powerful presence and style of someone accustomed to leadership. Such was this sixty-three-year-old African woman's intelligence, experience, and charisma that, after spending only two hours with her, I thought she might well one day become president of South Africa. No doubt my assessment was also influenced by the fact that she is currently the most highly placed woman in the exiled African National Congress, being one of only three women on its thirty-five-member National Executive Committee.

A teacher by training and many years of experience, Mompati gave up her profession in 1953, just one year after she had married and moved to Johannesburg to be with her husband. She felt she could no longer teach after legislation was passed in 1953 requiring that educators train their black pupils to fit into the subservient roles they were expected to play in South Africa. Mompati soon became a member of the ANC, and spent the next ten years working as Nelson Mandela's secretary in his and Oliver Tambo's Johannesburg law firm.

In addition, Mompati was active in the Women's League of the ANC before it was banned in I960, and was among those who founded the Federation of South African Women in 1954. Six years later, when the ANC was banned, she was asked by this organization to work underground, which she did for five months. When the ANC asked her to leave South Africa in order to learn certain skills they needed, she also agreed to do so since she believed it would only be for a year. She reluctantly left her two-and-a-half-year-old baby and her six-year-old son with her mother, her sister, and her sister's husband, and went abroad in September 1962. »With my children so young, I had no intention of staying away for more than a year«, she said emphatically. On the eve of Mompati's return twelve months later, because of events in South Africa which she describes in the interview, she was forced to realize that returning meant certain imprisonment. Her description of how she felt as a mother to be forced to live apart from her children for the next ten years are among the most moving passages in this book.

Mompati first became a member of the ANC's National Executive Committee in the 1960s, and then again in 1985. She is currently the administrative secretary of the National Executive, which means, she said, »that I have the very great responsibility of more or less administering the whole organization« Mompati's work for the ANC has made her into a widely traveled and very cosmopolitan figure. She lived in Lusaka, Zambia, working at the ANC-in-exile's international headquarters until 1976, after which she was sent to the Women's International Democratic Federation in the German Democratic Republic to represent the Federation of South African Women. She spent three years in the GDR at this time, and another three years (from 1981 to 1984) as the chief representative of the ANC in Britain and Ireland. Since then, Lusaka has been her main base.

Because of Mompati's role in the ANC, which many regard as the South African government-in-exile, what she has to say about her organization's position on violence and communism, two of the major preoccupations of international opinion, is of particular interest. Mompati also provides a vivid picture of the acute dilemma felt by many women in the anti-apartheid movement. On the one hand, she (and many others) recognize the seriousness of the problem of sexism women are faced with; while on the other, she believes that the national struggle, as she refers to it, is the priority. However, she also maintains that the women's struggle cannot be divorced from the national struggle and that national liberation is a prerequisite for women's liberation. Nevertheless, Mompati is an extremely articulate spokeswoman for one of the most common perspectives on black and women's liberation in South Africa.

Growing Up African

I come from a family of peasants and was born in a small village, Ganyesa, in the northwestern Cape between Mafeking and Kimberley. My father worked on the land in this village as well as in the diamond diggings. His work in the mines was periodical, so most of the time he was in the village. There were six of us in the family, three girls and three boys. One of the boys died as a child from a common children's ailment which doesn't necessarily kill children in other countries.

My mother only went as far as standard three [fifth grade]. My father, who comes from a family of thirteen, taught himself to read and write when he was working in the diamond diggings. I don't know what put the idea into his head that we should get an education, because no one in his village or in his family was educated, but he said that he wanted his children to live a better life than he had led, and he felt that education would make this possible. So he moved to a small town in Vryburg to be closer to the school we attended. Interestingly, we never considered this little town our home. The village was always home to us because our grandparents lived there. They lived to quite a great age— my grandmother until she was over a hundred. She was such a wonderful, strong person, and she had a wonderful memory. She would relate a lot of things to us like how they suffered during the Anglo-Boer War [1899-1902]; how they were treated by the soldiers; and how she had to carry her many children from one place to another with my grandfather.

My father died when I was fourteen, and it became impossible for me to continue at school. I had to work for a white family looking after their young daughter. The child was very close to me—you are really the mother of the white child in South Africa; and I think that she loved me because I was the closest person to her. I was with her all the time. I took her everywhere, played with her, and put her to bed. She had a sister who was about two years older than her, and these children were around me all the time. I hadn't had anything to do with white families before, but I became aware that the parents of these children treated me as something completely different from themselves. When I told them that I would like to go back to school, it didn't interest them. They sent me on errands, so I also had to deal with whites in shops. This placed me in the presence of older African people — whom I looked upon as parents because we Africans are taught that anyone older than you is a parent—who were sometimes humiliated in front of me. They stood there mutely not saying anything, and as a child I couldn't say anything if they didn't say anything. I couldn't stand another year of this, so I told my mother, »I don't mind what you do, but do something! Find money! I must go back to school!« I don't know how she got the money, but the following year she sent me to school.

Teaching was the cheapest profession for Africans to train for, so that's what I and my two sisters did. I started teaching when I was eighteen in a village fifteen miles away from my home. The children had to walk to school, some of them six miles each way every day. It was extremely cold in winter and extremely hot in summer, so these children had to walk these twelve miles in extreme circumstances. When you teach in that type of situation, you have to be a doctor, a nurse, a social worker, and an advisor. The nearest real doctor was fifteen miles away. You are the center of wisdom. Everybody comes to you for help, so you get to know the difficulties of these people.

On a cold winter's morning, I'd see the children come to school with only one garment covering their little bodies. It may have been the elder sister's dress or a shirt three sizes too big, and they'd sit there shivering. I was expected to teach them in these circumstances, and they were expected to learn. It used to break my heart. I was born into apartheid, and I grew up with it, and I knew these children were in this situation because of the racial discrimination in our country. Their parents worked very hard from dawn to dusk, but they couldn't buy more than what these children had. They couldn't feed them more than they fed them. And some children in my class died at an early age, six years, seven years, eight years. By the time I'd taught for a year, I'd seen many little lives ending. And I knew from my reading that children in other countries don't die from diseases like measles. They don't die from malnutrition. There was no need for these children to die.

As I mentioned, another distressing experience was going into a shop. The first thing the white woman or man would say to me was, »Annie, what do you want?" They didn't say, »What can I do for you?" They didn't ask what my name was. Because I'm black, any name would do for me. All this generated such anger in me, I wanted to shake them. My response was, »Yes, John, can you give me a loaf of bread?" That used to incense them! I started fighting back at a very early age. I think I was a rebel by nature. I didn't necessarily plan to say something like that, but the anger would well up in me, particularly when there was an old man in front of me who'd be asked by a young person, »Yes, John, what can I do for you?" »This is my grandfather«, I'd think, and this young person is calling him »John"! I wasn't only fighting my own battle but the battles of everybody else.

It's very difficult to say in what ways apartheid hurt me most. There were so many arrows striking into me all the time. If ten people are all shooting at you at the same time, one shot is not less painful than the other. To me, that's how apartheid attacks you as a child. The constant brutality of seeing whites push my people around when I knew this shouldn't happen, hardened me, made me grow up before my time, learn to defend myself so I wouldn't get destroyed inside, and forced me to live for the future when I could change these things.

Political Activity: The African National Congress

When I was a student, I became a member of the students' union, which fought for the rights of students. And later I became a member of the teachers' union. I started thinking that things could be changed when I became a teacher, but I wasn't yet thinking of political change. At that time I still believed there was a place for my people somewhere in the South African setup. I thought that we could fight for better working conditions for teachers. But the longer I taught (I taught for eight years in all), the more I realized that under apartheid there is no place for me or my people.

In 1950, a teacher who was a member of the African National Congress came from Mafeking to teach with us. He introduced us to this organization. It hadn't occurred to us that we could work for the ANC. Teachers weren't allowed to be members of political organizations because we were supposed to be civil servants. But it was possible to work as an associate without taking the official membership. There were a number of us in our early twenties, and we did just that. We started by raising money for the ANC.

But as for how I became politically conscious, I think that politics just caught up with me. The racial discrimination, the brutalization of the African people around me, the contempt and the arrogance of white South Africans, made me defiant and eager to fight back.

My marriage in 1952 meant moving from a fairly small, quiet town to a big city where people like Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu and many others had been arrested for their participation in the Defiance Campaign. I joined the ANC properly in 1953, and I also became a member of the Women's League of the ANC. I couldn't go back to teaching because the Bantu Education Act [which imposed a highly inferior education on Africans in 1953] had been passed, and I refused to teach according to this law. Since there were no secretarial schools for Africans, I had to attend a private school to learn to be a shorthand typist.

I got a job [in 1953] in the law firm of Mandela and Tambo—the first African attorneys' partnership in South Africa. I was a typist in their office and a secretary to Nelson Mandela. It was a very wonderful experience to work with them because they were the attorneys who dealt with political cases, so everybody went there: people who had money to pay for their cases and people who didn't. They were very popular and very good lawyers. We always said that if they had been interested in money, they would have been among the rich in South Africa. But they chose their mission in life as leaders in the struggle because they felt that a rich slave was no better off than a poor slave. Working with those two leaders was one of the best times of my life. It meant a lot to me to come into contact with ordinary African people and their political problems, and to come into contact with people from all walks of life. These two men were not just leaders of the black people and of low-income people. They were leaders of everybody. People of Asian origin and white people came there, too. That's where I met most of my friends from other racial groups.

I worked in that law firm for ten years until our president, comrade Oliver Tambo, left the country to open an ANC mission outside. Then, under the instructions of comrade Nelson Mandela, I and the accountant closed the firm. We took the files to other attorneys and asked them to deal with them. I then went to work for the Defence and Aid Fund [which contributed funds for the legal defense of political activists] before it was banned.

Motherhood and Exile

I was expecting my first child during our campaign against Bantu education in 1954. I was so busy running around, I always remember my colleague, Tambo, saying to me, »One day you will drop that baby and jump over it whilst you are still running« But I was very healthy, so it didn't worry me. And after the baby was born, I was just as involved with my work. We women always used to carry our babies to whatever work we were doing.

In September 1963, after I had been abroad for a year at the request of the ANC to work in their mission, I was all set to return to South Africa, hoping that I would be able to slip into the country without the police knowing that I had come back, but knowing that maybe I would spend a few months in prison because I had left without a passport. Then I learned of the Rivonia arrests.[6] Every week they were picking up more people, until most of the leaders were arrested. Then the man with whom I had worked underground for those five months became a state witness, so the ANC told me not to come back. I said I had to return to my children, but they said there was no point because I would just go to prison. So the next time I saw my children was ten years later. The baby was twelve and the older boy was sixteen.

I used to get ill thinking about my children. After ten years of separation, I wrote them a letter and gave it to somebody to hand-deliver to them. In it I said to them, »If you want to join me, I'm in Botswana. You know what to do. Just cross the border and come over« So the children packed and came to join me. It would have been very difficult for them to join me sooner because before then, Botswana and Zambia were not independent. Only Tanzania was. When I had left South Africa to go to Tanzania, it was very difficult to get there. Many of our people were arrested in Northern Rhodesia [now Zambia] or Southern Rhodesia [now Zimbabwe] and sent back home. If you arrived in Dar-es-Salaam [in Tanzania, East Africa] you always considered yourself lucky. I had been one of those lucky ones.

I had left a baby of two-and-a-half years and a child of six years. I discovered that there's no way that you can see the growth of your children in absentia. You always think of them as being the age when you left. It doesn't matter how many years pass. When I met the twelve-year-old after ten years it wasn't too bad; I could still cuddle him. He hadn't shot up as one would have expected. But my other boy was a tall sixteen-year-old. I didn't know him. I didn't know how to behave toward this boy. It broke my heart. And neither of them knew how to behave toward me. I was watching their reaction, and they were watching mine. I can never explain the emotional suffering of this meeting. It is extremely painful for a mother to miss her children's childhood years. I died so many deaths. I felt, »Good God, the South African regime owes me something, and that is the childhood of my children!" But I'm not unique. Indeed, I'm lucky. I met my children after ten years. There are those mothers who never meet their children again, who just hear that their children are dead. In contrast, we were able to sit down and discuss what happened, and they were able to begin to understand why I had stayed away from them for ten years. We could build a relationship again. They came to live with me here in Zambia in 1972. There are many parents who never get that chance.

The Federation of South African Women

We founded the Federation [of South African Women] because we felt we needed an organization for all women of South Africa. But because the African people are the majority in South Africa, the ANC Women's League was its biggest affiliate. However, we also had very strong membership from the Indian women's organization, the Coloured women's organization, white women from the Congress of Democrats [an organization for white radicals], and women from the trade union movement. And we had a working relationship with women from the Liberal Party of South Africa who used to come as observers when we had conferences, and women from the Black Sash.

Working with all women in the federation enabled us to realize that there were no differences between us as mothers. We were all women. We all had the same anxieties, the same worries. We all wanted to bring up our children to be happy and to protect them from the brutalities of life. This gave us more commitment to fight for unity in our country. It showed us that people of different races could work together well.

When it comes to the work of liberation or any work in any society, men are always in the leadership positions. There are very obvious reasons for this — not only amongst Africans but amongst whites, too. Usually it is men who get a better education than women, so they know more and become more articulate and are more easily able to get jobs. And there's the historical tradition of women's place being in the kitchen whilst men's place is in leadership. So we felt that, even in an organization like the African National Congress where there is no discrimination based on sex, we needed to have an organization which would tackle problems that are specific to women. We women have always been on the bottom rung. We felt that we needed to educate our women that this is not our place. Women have occupied that place by accident of history, but we can participate and we can lead. But the oppression of African people has always been the key problem in South Africa. We are not on the same level as the white, Indian, and Coloured women who were also members of the federation.

Fighting the Pass Laws for Women

Because the pass laws formed the cornerstone of our oppression as Africans in South Africa, the Federation of South African Women took up this issue. Apartheid has to have a reservoir of cheap black labor, and the pass laws helped to provide this by controlling the movement of African people. Africans were completely controlled by the pass laws, including where they could stay and where they could work. So when we realized in the early 1950s that the pass laws were going to be extended to women, we knew we had to fight this.

In taking up this struggle, we were taking up a powerful tradition. Already in 1913—one year after the founding of the African National Congress—[African] women had been put into jails in Bloemfontein in the winter of that year. Their men wanted to bail them out, but the women refused, saying, »We will serve the sentence. We have burned the passes because we don't want to be controlled the way our men are controlled« That's why women didn't have to carry passes like the men for all those years. And in 1929 and 1953, the women fought against passes again. They were successful until, I think, 1962. It was only after the government had amended the laws in such a way that anything one did could be seen as sabotage, that they were finally able to extend passes to women. So the pass was a very important issue to the Federation of South African Women as well.

Fighting Bantu Education

Bantu education was another issue the federation addressed. [Hen-drik] Verwoerd, who was the minister of so-called Bantu affairs at that time, said, »There is no place for the African in the European community, save as certain forms of labor« His idea was that when black people are educated, they see the green pastures on which the whites are grazing and become envious, then rebellious. So Bantu education was instituted to make it very clear that black children had to be educated to know their place in South Africa. They must only be given enough education to be useful to whites, which meant being manual laborers and being able to carry messages intelligently for the white population. The African National Congress itself had taken up the question of Bantu education even before the Federation of South African Women was founded. Indeed, the program of action of the federation could not be different from the program of action of the African National Congress and of its Women's League, because removing racial discrimination was the first priority.

The Role of Women in the Struggle

Even in an organization that supports the liberation of women, we have had to work hard to build the confidence of our women, because we are victims of history, victims of our traditions, victims of our role in

society. Despite this, African women have always been part of the lives of their communities. Actually, they have been the strength of the communities, but they've always been a silent strength. But in the past years, our women have come forward and taken the lead more. They are not just supporting the men and pushing the men in front.

The National Executive is outside the country. One of the reasons there are only three women [out of thirty-five] on it is that very few senior women have left the country. But also there are a lot of women leaders inside the country who, if we had a free South Africa, would be on the National Executive. So we can't really judge the representation of women in leadership positions by looking at the National Executive of the ANC. Secondly, we have to continue to fight to put our women into leadership positions and to make them more able so that they can lead and articulate their problems. We still suffer from the old traditions.

Inside South Africa, we have Albertina Sisulu, [see chapter 10], Frances Baard [a trade-union leader who was jailed and banished in the 1960s], and Helen Joseph [see chapter 15]. But also, the very reason for forming women's organizations is to try to change the tendency for men to always be the leaders. Even in the most developed countries of the world, men are in the leadership positions. How many women are in the British government today? That's why Margaret Thatcher makes world history. It's a pity that she's not a very good example of women's leadership. And how many women leaders are there in the United States? So this is a historical phenomenon which we have to attend to.

About two years ago, we were discussing with the leadership of the movement what liberation for the people of South Africa really means. Will women find themselves in the same position as they have always been? Or do we see liberation as solving the conditions of women in our society? We have brought these questions up with our own leadership because we want them discussed now. If we continue to shy away from this problem, we will not be able to solve it after independence. But if we say that our first priority is the emancipation of women, we will become free as members of an oppressed community. We feel that in order to get our independence as women, the prerequisite is for us to be part of the war for national liberation. When we are free as a nation, we will have created the foundation for the emancipation of women. As we fight side by side with our men in the struggle, men become dependent on us working with them. They begin to lose sight of the fact that we are women. And there's no way that after independence these men can turn around and say, »But now you are a woman«

If you look at the role of women in South Africa, you find that they are the breadwinners because the men are not there. They also bring up their families because the men are either in prison or they are working away from home. And they are in the fight for national liberation. They are the supporters of those who are fighting in South Africa, and they themselves are fighters. They are in Umkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the African National Congress. They are in the community organizations, the health-improvement organizations, the organizations that look after prisoners, and those that look after the parents of prisoners, encouraging the parents to come together and attend to prisoners. They are in the churches, they are in every organization in the country that you can think of. For us, this is one of the first victories as a people. We've got our women feeling that the liberation struggle is their responsibility, and also that they've got a responsibility to their nation to bring up children into a happy world; and since there is no happy world for us, to bring about that happy world. We have seen that, because of this increase in women's participation, our movement has become stronger. The community organizations inside the country have organized alternative structures. For example, in places where the usual services are no longer being rendered because the people have refused to pay rents, the people themselves have made it possible for those services to continue. An infrastructure has been created by the people, and our women are the strength in these structures.

In Angola, for example, the majority of women were illiterate. Although the women who participated in the struggle were not educated, they had confidence. It wasn't a confidence brought about by being able to read or write, but a confidence from being part of a movement that did away with the oppression by the Portuguese fascist regime. They drew up their own programs of what they wanted to do, and they actually won a medal from UNESCO for the way they tackled illiteracy. They could only do these things because they were free as women to move forward with their own programs. And they were respected. A number of the women who had participated in the struggle were given positions in the ministries and the central committees, even those who didn't have a high-level education. So, what happens to women after liberation depends on how much women are part of the liberation struggle itself. But the national question is our central task.

The African National Congress and Communism

The South African regime has always been paranoid about communism. My first understanding of communism was that communists are the people who fight for their rights and who support the struggle of people who want freedom. For example, in the past if there was a strike for better pay, there would be a witchhunt, and people would be arrested and fired because they were communist. It didn't matter what you did, you would always be called a communist.

The Communist Party of South Africa has been banned for many years now. Some of their members are also members of the African National Congress. As far as we're concerned, this has never been a problem. Some of them have been among the finest people I know. For example, a person like Moses Kotane was a communist and also a leader of the African National Congress, but he never used his position in the ANC to organize people into the Communist Party. What was primary for him was the liberation of the people of South Africa.

The African National Congress is a movement which brings together people from all walks of life, people of different races and religious beliefs who are against apartheid. When we have liberated our country, when we are free, maybe we will begin to look at what we think of communism. The issue of communism has never interfered with our work. But we know that every time anyone is active, they are considered a communist. When we do anything intelligent, it is seen as influenced by Moscow. If we organize a campaign that is successful, then so-called troublemakers and communists are held responsible, not the movement.

I have been described as a moderate with strong nationalist leanings, and I have also been described as a communist. Other members of the ANC have been called communist because they were trained in the Soviet Union—as if that made them communist. Meanwhile, for us, the question of who is a communist is irrelevant. The relevant question is who is actively involved in the struggle for a new South Africa.

The Issue of Violence

It is important to know why the African National Congress is involved in an armed struggle. For a very long time, we thought we could fight for our liberty peacefully. We thought we could discuss, plead, petition, and demonstrate for it. The last thing that Nelson Mandela did before he was imprisoned [in 1962] was to call for a convention where all South Africans could come together to discuss what should be done. The South African regime rejected his proposal. All the time that the African National Congress was using peaceful means to try to bring change in South Africa, the reaction from the regime was violent. People were shot at peaceful meetings. I can't count the number of meetings of the Women's League of the ANC which were surrounded by armed police peering through the windows with their guns pointed at us. Since I wasn't used to guns, I didn't see the danger of this at the time. Nor can I count the number of meetings of the Federation of South African Women when we were given five minutes warning at gunpoint to close our meetings. We knew that if we didn't do so, we would be shot. This violence also occurred when our people were arrested. Thousands upon thousands of South Africans have died violently at the hands of the police. We've got hundreds of children in prison today. What crime can be committed by an eleven-year-old that he should be in prison? Teenagers have been imprisoned in Robben Island's maximum security prison. What crime can be committed by a teenager to justify this? When our people carry to the graveyard the coffins of their loved ones killed by the police, they are shot on the way or at the grave site itself. As they are burying one, others are falling dead.

But it's not only direct violence that we are concerned about. There's also the violence of the conditions of living in South Africa. The deaths of our children from malnutrition, the short life span of our women and our people, the violence of the education where our children are condemned to a life of ignorance. The violence of the working conditions of our mine workers who bring gold from the bowels of the earth, but whose safety is not even thought about. How many of them have died from miners' phthisis or because the mines have fallen in on them because the necessary precautions were not taken? The whole life of an African person is a life of violence! The African National Congress looked at all this, including the fact that we have done everything to try to speak to the white people of South Africa. But they have even closed our mouths. Our people are banned and banished. Our organizations are outlawed. Even the nonviolent methods which we had were made illegal. We had to look at our children suffering and being shot by the police, but what could we do as a people to change the situation? We decided that, if the gun is what the South African regime has used to rule us, it will have to be the gun that breaks that rule.

On the issue of necklacing [murder by placing a burning tire around someone's neck], sometimes people take actions which they would not have taken under normal conditions. A few people are using methods that they would not have used had they not been faced with so much violence. For example, a young man put a limpet mine in a supermarket, and five whites died. And the whole world went berserk. We pointed out that forty-one black people had been killed in Lesotho in cold blood by the South African regime. And this boy who put a mine in the supermarket had played with many of those people who were killed in Lesotho when they were children. They had all grown up together. If they had been shot fighting the police with arms, that would have been different, but they were sleeping! And this young man said in court that he couldn't take what had happened to his friends, so his mind became closed to any reason. It's very easy for the world to look at what the African National Congress or what the black people in South Africa are doing, but not at the scale of the violence against us. The South African townships are occupied by the police and the army. There's violence every day. The South African regime pays young black people to kill those who are struggling for better conditions. It's a hungry society, so it's not surprising that some accept this money so that they can eat.

And some of the violence which is often blamed on the African National Congress is really perpetrated by the police. They necklace people, and then they say it's the ANC. They kill people, and then say it's the comrades [young radical opponents of apartheid]. This has been proved a number of times where they have been caught redhanded. But the press is not even allowed to report this, and this censorship is even worse now under the state of emergency. The ANC has a very clear policy that we only attack apartheid's instruments of repression and its supporting structures—the police, the military, and the economy of the country. We believe that if we destroy the economy of the country, we are destroying apartheid. If innocent people are hit, it will not be because our policy has changed, but because there is a war going on in South Africa. And the world must recognize that where there is a war, a lot of civilians suffer, as they did in Europe in World War II.

Women and the African National Congress

»We women students actually accused the men of being

cowards because time and again it was us who had to be

in the front of the demonstration facing the guns

and the bullets«

MAVIVI MANZINI

...has been working full-time for the Women's Section of the African National Congress since 1979. She is a thirty-one-year-old African who escaped from South Africa in 1976 (as she describes here) when she was twenty. She obtained a B.A. degree in political science and sociology from a Zambian university in 1979. A year later in 1980, Manzini married a man who is now working for the ANC Youth Section. Their only child was born in 1984. Although Manzini's three siblings were, like her, involved in the student movement in South Africa, she is the only one who now lives outside the country.

Manzini speaks of her work in the ANC underground and is particularly informative about how the ANC's Women's Section (to be distinguished from the earlier Women's League) is organized, and what its current thinking is about the status of women and women's issues. I was impressed by her willingness to talk about the fact that sexism is a serious problem within the ANC-in-exile (for example, ANC women often feel they cannot attend meetings because of their domestic responsibilities), but even more serious inside South Africa. Manzini's thinking on this question suggests the heartening possibility that the ANC-in-exile may be significantly more progressive in understanding the importance of women's liberation than its sister organizations inside the country.[7]

In this connection, Manzini reports that the Women's Section is currently engaged in drawing up a bill of rights for women. They have been both gathering information about family codes and laws on women in different countries in order to try to arrive at the best possible bill of rights for women, and also seeking input into this document from women in South Africa. Manzini said that it would include policy statements about lobola (paying to obtain a bride) and polygamy, both controversial issues in South Africa. White South Africans have typically responded to African traditions in such a heavy-handed and racist manner, that many African people are defensive about them. Africans have the task of deciding which traditional practices are positive and to be preserved, and which are negative (even if they were once positive) and in need of change. Manzini was definite that the traditional practices of lobola and polygamy are oppressive to women. »If we want equality«, she declared, »lobola has to be scrapped«

With regard to the ANC-in-exile in general, Manzini reported that it has been growing »because lots of people are leaving the country« The ANC community is even larger in Mazimbi, Tanzania, than in Lusaka, because this is the location of their school. It is, however, too dangerous for ANC people to live in countries close to South Africa, and thus relatively few are living in Zimbabwe. My own experience in Zimbabwe helped me to understand this in a personal way. The ANC member Phyllis Naidoo invited me to stay with her, but warned me that it was at my own risk, because the ANC offices had just been bombed the previous day. When I went to visit her at her home, two soldiers were on guard. Even in faraway Zambia, ANC members are not safe. »According to the Boers«, Manzini explained, »they have the capability to strike up to the equator. So at times we have to live in hiding, and we live scattered throughout Lusaka«

Even those in exile, then, have to fear the power and military might of the South African police state.

Growing Up African

I was born in 1956 in Alexandra township in Johannesburg, then moved to Soweto when it was established. I am one of eight children, of whom only four are still alive. I suffered from polio when I was about two years old, and spent most of the next four years in hospital. But from the age of six, I was well and started at school.

Apartheid affects people from childhood. We lived in a terrible part of Soweto, and although my father and mother were both teachers, they had a very hard time making ends meet. Sometimes there'd be no food. Later I became aware that our situation was connected with the political system, but I understood it only as poverty when I was young.

My school was quite a distance from my home so I had to wake up very early in the morning to get there. There were only about four school buses to collect people all over Soweto and drop us off at different places. By the time the bus got to my place, it was often full. On the way to school, I'd see white school buses that were empty, so I started to question this difference. As I grew up, I began to notice that it was our people who were working so hard but who continued to suffer, and I realized that my parents were getting a raw deal. The ANC was banned when I grew up, but I learnt about it from my parents who were very active members in the 1950s. They would tell us about detention, the Mandelas, and how difficult it was to do anything against the regime.

Political Activity

In 1973, when I was seventeen and at high school, I got involved in the South African Student Movement. I continued with this involvement when I went to Turfloop University in the northern Transvaal. The South African Students Organization, SASO, had been banned on campus by the university administration in 1974 following a rally. The students had demonstrated in solidarity with the people of Mozambique when they won their independence from Portugal. Most of the students who participated in this demonstration were expelled. After that the Student Representative Council, which had been the mouthpiece for student grievances, no longer existed because most of its members were among those expelled. Many of them went into exile, but some were tried and sentenced to five years in prison.

It was a very difficult time to be politically active on campus, but some of us decided that we wouldn't be silenced. We organized SASO meetings in a church off the campus to discuss the state of student rights, and this kept at least some political life going at the university. I was in my second year at university when the Soweto uprising started in 1976 and spread throughout the country. When the high school students started demonstrating against the Afrikaans language being made the medium for their education, we at the university wanted to show our solidarity with them, so we organized a demonstration on 18 June —two days after the shootings in Soweto. The police came on campus and arrested and detained many students. Although I was involved in the planning of this demonstration and participated in it, I wasn't detained on this occasion.

I became involved in the ANC underground earlier in 1975. I was in a unit with four other campus activists. We carried out tasks to assist the ANC, especially Umkhonto we Sizwe, by reconnoitering and giving them information about the whereabouts of the police, especially in the northern Transvaal area where there are military bases. I lived around that area at that time and knew it very well.

We got most of our political education from the ANC, who supplied us with literature that was otherwise unavailable in the country. After reading it, we'd pass it on to others in the student movement. We also used to listen to Radio Freedom [8] which helped us with our political development.

We'd talk to other students about the ANC because we were convinced that the time had come for our methods of protest to go beyond demonstrations. Most demonstrators end up being detained or shot without having really contributed to the struggle. Of course we had to be very careful who we approached. Because the ANC was a banned organization, it meant five years in prison if we were found to be involved in it.

Then one of our unit members was detained in May 1976 before the Soweto uprising. The police had trailed him when he went to meet with the ANC outside the country. They detained him at the border on his way from Swaziland. We informed the ANC of his detention, but decided to remain in the country because it is so difficult to leave. We hoped that they wouldn't come after us, but if they did, we thought there wouldn't be a very heavy charge because we didn't actually carry out any operations, we had only reconnoitered.

I think they tortured our comrade. He resisted talking to them for a long time, but he broke down after two months, resulting in detention for the rest of us and a ten-year sentence for him. I was detained on the third of July. It was the day I was supposed to have left for a SASO conference. The police had been watching my movements and knew when I would leave, so they picked me up from my home that morning. After the university was closed down, it became difficult to maintain contact with the other comrades in my unit so I didn't know that they had been detained before me. So by the time they took me in, the police already had a whole file on me filled with information that had been sucked from my comrades.

I was transferred to another police station out of my home town where I was held in solitary confinement. After leaving me in my cell for about three days without questioning me, the police repeated the same questions about the other people in my unit that they had asked me the first day. When I denied something, they'd open my file and read out the information they had been given. I felt very helpless, even though they didn't actually have a lot of the most significant information.

But they knew that I was in touch with the ANC and had propounded its aims and objectives amongst the students. I was afraid that if I continued to deny everything, they'd torture me. To be held in solitary confinement, to be given food only once a day, to be taken out of the cell time and again for questioning, is itself torture. But I think they didn't hit or torture me further because they thought there was no more information to extract from me.

They kept me in detention for two months. One day in September 1976, I was told, »We are releasing you, but you must report to the police station every day to tell us where you are going and what you are doing. And we might call you in later« They wanted to monitor my movements, and I think they planned to charge me later. I was released with the three other people from my unit including Joyce Masamba, the only other woman member. One month later, they detained Joyce and the other two comrades again. Immediately after I learned this, I left the country.

Two of my comrades were charged with terrorism for aiding the ANC and were sentenced to five years in prison. The other two, both of them men, were used as state witnesses. Joyce is presently in detention again under the 1986 emergency regulations, together with her sixteen-year-old son.

Other people connected with the ANC were supposed to help me escape, but they were all in detention. So I didn't know how to leave or whom to contact. I was left in the lurch. But I finally managed to contact people who assisted me in working out an escape route to Botswana. Botswana is quite a distance away from where I was in the northern Transvaal, but I had a few pennies, and these people gave me a few more pennies, and I took a train which stopped at a place about an hour's drive away from the border.