»I always draw a parallel between oppression by the regime

and oppression by men. To me it is just the same.

I always challenge men on why they react to oppression

by the regime, but then they do exactly the same things

to women that they criticize the regime for«.

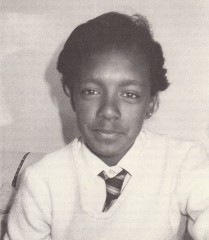

SETHEMBILE N.

The Speakers in this section focus more on some of the issues some political activists are tackling than on organizations. Sethembile N.[1] [pseudonym], for example, shows why Chief Gatsha Buthelezi's Inkatha movement is seen by both the government's security branch as well as anti-apartheid groups as a major obstacle to the South African liberation struggle. Since Buthelezi—who has a significant international reputation, particularly in the United States—opposes divestment and indeed encourages foreign investment in South Africa, claiming it is good for black people, the international business community has enthusiastically embraced him. Business leaders ignore the fact that all the black leaders of the anti-apartheid movement are in favor of sanctions and divestment. I realized how important it is for the international community to hear about this other side of Chief Buthelezi. It was impossible, however, to find a Zulu woman who was willing to talk about him without using a pseudonym, so fearful are critics of retaliation by him or Inkatha—the movement that he heads.

While Sethembile N. chose to use a pseudonym to protect her life, Hettie V., a rebel against her Afrikaner heritage, decided not to use her real name in an effort to keep a low profile so as to continue with her political work as long as possible. Although not the only Afrikaner I interviewed, Hettie V. is the only one represented in this volume. She has a fascinating tale to tell, starting with her learning to shoot at the age of ten with other Afrikaner children who were members of an organization called the Young Voortrekkers.

Rhoda Bertelsmann-Kadalie, a Coloured woman, describes the consequences of her marriage to a white Afrikaner both before and after intermarriage became legal. One of the much-heralded reforms of the current government was to repeal the Mixed Marriages Act, which outlawed marriages between members of different races, along with the so-called Immorality Act, which had made interracial sexual relations illegal. Bertelsmann-Kadalie shows how these reforms have not stopped the harassment of racially mixed couples.

Leila Issel, the thirteen-year-old daughter of Shahieda Issel [see chapter 4], describes her political activity from the age of seven, and the police response. Since children are playing such a crucial role in the South African liberation movement, I felt it important to include the voice of at least one child.

Finally, Sheena Duncan, a prominent leader in the Black Sash with an extraordinary fund of information about the racist legal system in South Africa, describes the appalling scope and destruction that has resulted from forcing millions of people, mainly Africans, to move from their homes to uninhabitable dumping grounds. This massive dislocation is part of the government's insane dream and malevolent belief that apartheid can and must be implemented.

A Refugee from Inkatha

»Inkatha is even worse than the Special Branch.

The Special Branch detains you and puts you in prison,

but Inkatha destroys you...

Refugees used to live outside the country,

but because of Inkatha, many people are now

refugees from Inkatha inside the country«.

SETHEMBILE N

...is, as a Zulu, particularly vulnerable to Inkatha's efforts to punish Zulus who belong to UDF-affiliated groups instead of showing loyalty to their Zulu chief, Gatsha Buthelezi. Thus, she finds it necessary not only to use a pseudonym here [2] but to hide out illegally in the so-called white neighborhoods of Durban. In this interview, Sethembile N. describes the events—including the murder of a friend's father—that led to her decision to become a refugee from Inkatha and go into hiding.

Thirty-four years old in 1987, Sethembile N. is the mother of three daughters, the eldest of whom is fourteen and the youngest, seven. A teacher for many years before her political activities made it impossible to continue, she was also a battered wife who left her husband and has become an able and dedicated leader in the National Education Union of South Africa. Sethembile N. describes both of these experiences in some detail. Although I didn't ask her whether she considers herself a feminist, her active and outspoken commitment to gender equality earn her this label in my mind. The stories of Sethembile N., Gertrude Fester, and Anne Mayne lead me to wonder whether women who are battered or raped are more likely to become feminists, or whether feminists are simply more willing to reveal these experiences. (I did not specifically ask about experiences of male violence.)

I interviewed Sethembile N. in the Durban house I was staying in one day after the election on 6 May 1987. The UDF had called a national stayaway to protest the all-white elections and to highlight their demands for the unbanning of the ANC, the release of the leaders in prison, the return of those in exile, the lifting of the state of emergency, and the withdrawal of troops from the townships. Sethembile N. described herself as »really inspired« by the effectiveness of the stayaway. »Although the South African Broadcasting Corporation would underplay what is happening,« she said, »they reported that sixty percent of the workers in Natal participated in the stayaway yesterday. This degree of support was unexpected because of Inkatha's repression in this province. The participation was highest in the Transvaal, and in Port Elizabeth and East London it was eighty percent to one hundred percent. This morning Capitol Radio said that the participation today is even higher. So it has been very successful«. Sethembile N. has a strong personality - direct, assertive, energetic, exuberant, and very present — and is definitely a leader. May she have the opportunity fully to realize this ability.

Growing Up African

My father is illiterate, and my mother was a domestic worker until her health got bad. When I was only eleven or twelve years of age, I had to work during my holidays for the white holiday makers. I washed dishes and looked after their children to help pay my school fees. My parents had to save all their money to be able to send me to boarding school for standards nine and ten. I started nursing after I matriculated. But I quit after three months because I couldn't take the regimentation. When I was seventeen or eighteen, I went to work in a factory for five rand [$2.50] a week. Then I decided I wanted to be a teacher. Because I had no money, I had to work as a private teacher for five years before I could get my training. I was also never able to study full-time at the University of Zululand for financial reasons. I found it very tough to study for my B.A. courses after work.

I got married in 1972. I was interested in politics during my married years but remained passive because my husband wanted me to confine myself to going to work and household chores. He and I were both teachers, but he would go and drink after work, while I was expected to go home and look after the kids, do housework, then be scolded for having ironed a blue shirt rather than a pink one. He felt threatened if I wanted to go to a political meeting, so I was prevented from involving myself as fully as I wished.

When I tried to further my education, my husband tore up my notes and said, »You want to make yourself better than I am«. He was violent and drank a lot. I have a scar on my head where he stabbed me with a knife. I was staying with my in-laws and sitting in the lounge peeling a peach with a knife. My husband came into the room and said, »Why are you looking at me?« Then he picked up the knife. Usually I ran away from him in these situations, but that time I wanted to see if he intended only to threaten me, but he stabbed me for no reason.

If he discovered that I was talking happily with his mother, he would say, »Are you gossiping about me? You are against me«. When he drank alcohol, he felt threatened and inferior. Sometimes he was violent toward me seven days a week. Most of the time I wanted to end the marriage, but society always expects a woman to persevere. I had to wait until everyone realized that things were very tough for me, otherwise I would have become an outcast.

In 1981, I said »To hell with everyone!« and I divorced him. But getting away from him was very difficult. I had to sneak out of the house and leave the kids with him. I knew he was a drunkard and that anything could happen to them, but I had to save my life. I went to the magistrate who was fortunately very sympathetic about my reasons for leaving. He said, »Do you want your kids?« I said, »Yes«. After about a week, a court order was issued requiring my husband to bring the kids to the magistrate's court and hand them over to me. Then I legally handed them over to my mother. I didn't even need a lawyer to fight the divorce, because I had such a strong case against him. He was very overwhelmed by this and has never been brave enough to approach me himself since then—though he has sent people to tell me he wanted to reconcile.

Political Activity

I taught Zulu [one of the major African languages in South Africa] and became very involved in education politics after my divorce. As a literature teacher I was able to bring up relevant issues in class and to use methods that conscientized the students by encouraging their creativity and critical thinking. Since 1984, I have been the chairperson in Durban of a nonracial teachers' organization called NEUSA — the National Education Union of South Africa. Teachers who belong to NEUSA have to be quiet about their membership because we challenge the government's system of education. NEUSA is the only nonracial teachers' union in Natal. Most of its membership is black because we are the most oppressed. We have a lot of support from students and a great deal of credibility amongst the communities.

In the northern Transvaal and in the eastern Cape, there was a time when the students would ask a teacher, »Are you a member of NEUSA? If not, get out!« We don't separate politics from education but see education as part of politics. Right now we are discussing the question of »people's education«. We are concerned about education for liberation and education after liberation. But since we are not in a position to take control of the education system, the first step is for our people's education programs to run parallel to the official system of education that exists now. We are critical of the biased history syllabus that only begins after the arrival of Western people in South Africa and that sees black people as troublemakers who stole the sheep of the white people. People's education tries to rectify these kinds of biases.

The government has now banned the very term people's education because they consider it to be teaching communism and revolution, so the materials we compile cannot be used yet. But before the state of emergency was declared, people's education was being taught in some schools in Soweto. After it, the South African Defense Forces have been present in the schools, which has made it very difficult to implement our programs. So we have to plan weekend workshops for students on topics like democracy within the schools, the history of the educational struggle in South Africa, and so on.

The recent state of emergency has hit us very hard. Most NEUSA teachers have been kicked out of school. Last year we could not even afford a national conference. One of our NEUSA members was called into the security offices simply for addressing the teachers about NEUSA. I was forced to resign from teaching in January [1987], which is what so often happens to NEUSA teachers. My school was closed down last year in September because the majority of the teachers there were NEUSA members and the rest were supporters. Many of us were transferred to schools in distant places. My friend Tozi Dlamini was sent to Zululand to teach at a school whose principal was a member of Inkatha from KwaMashu, where her father had been killed by Inkatha. I was transferred to Ermelo primary school, which is near Swaziland. If I refused to go there, I was out of a job.

Some teachers went where they were sent only to find no accommodation had been prepared for them. Others were told by the principal, »I don't know anything about you«. This is what happened to Tozi. The school chairperson said to her, »I don't want you. If the department is interested in giving us an additional post, they should tell us, and we will look for a teacher we want«. So they sent her up to Ermelo instead. Our lawyers fought this case, so she was then transferred to Pietermar-itzburg, where she teaches in a primary school, although she is a secondary schoolteacher with higher qualifications than anyone else in the school. They have her teaching sewing.

I have a job now that provides academic support, financial support, and assistance in finding accommodation for disadvantaged, mainly black students. I will have to keep this job, but my main interest is in education, and I miss teaching because I enjoy the interaction with the kids, and they enjoy it, too.

Gatsha Buthelezi and Inkatha

A significant problem in Natal is that most African schools in this province are in the KwaZulu area [the Zulu »homeland« run by Buthelezi], and Chief Gatsha Buthelezi has said that teachers' jobs will be threatened if they join our union. A bill was passed in the KwaZulu parliament saying that teachers who get involved in politics will be sacked. In 1986 the teachers in KwaZulu were forced to sign pledges saying that they would not denigrate or villify Buthelezi's name, the KwaZulu parliament, or Inkatha. As well as the pledge, teachers had to make an oath in front of a commissioner of oaths.

Inkatha is not popular because it is tribalistic, and the chief minister, Gatsha Buthelezi, is not democratic. Most of the people who are involved in Inkatha don't understand politics and what Inkatha is all about. They join to get jobs or for business reasons. A lot of information about Inkatha attacks are leaked by Inkatha people because so many of them aren't very committed to it. Only about two percent of the Zulu people are voluntarily Inkatha members. Pensioners won't get their pensions in KwaZulu unless they are card-carrying members. And at the beginning of each year, when students have to pay school fees, there is a fifty-cent fee for Inkatha. The lists of students and pensioners are then used by Inkatha to make the membership appear very large. But it's not a voluntary membership.

The Amabuthos, the Inkatha vigilante group who physically attack people, are not even members of the organization. They are migrant workers and unemployed people. Inkatha is able to get their cooperation because they need permission to stay in town. They are also rewarded with money and beer. The press interviewed the Amabuthos who attacked those of us attending the National Education Crisis Committee conference, and many of them said, »We didn't know what it was about. We were just told that we must get into the bus«.

In January 1985, the examination results of our standard ten students were withheld by the Department of Education. An Education Crisis Committee consisting of parents, students, and teachers was formed to deal with this, and I was one of the two teachers elected. We demanded that the Department of Education release the results of the students' examinations, but they refused. One day a woman phoned us to say that the police had told her that Inkatha would fix us for being the instigators of the boycotts by the Durban school kids who were protesting the withholding of their exam results. She asked them, »But why do you say Inkatha? Isn't Inkatha involved in the liberation struggle?« The chief of the Special Branch, Drane Meyer, said, »No, Inkatha is working with us. Just give us three months«. We were very frightened by this threat because we feel that Inkatha is even worse than the Special Branch. The Special Branch detains you and puts you in prison, but Inkatha destroys you.

I lived in a place called Hambanati when I was still married. It is about forty kilometers from Durban. In 1984, Inkatha attacked all the people they considered UDF elements in Hambanati and burned down their houses. The whole UDF community in Hambanati was uprooted and their houses destroyed. I was one of those who lost my house there. I was not staying there at the time because I had to be near Durban for study purposes, but I had intended settling there with my kids after I had completed my degree. I didn't go back there, but most of the people wanted to return, so there were negotiations between Inkatha and the UDF about this. But the people who returned to Hambanati were attacked by Inkatha again, so they had to move out permanently.

In May 1985, I was living with two other women in a cottage in the Umlazi township. We were living under great tension. If there was a movement outside, we thought, »Oh! Inkatha has come«. Then we thought, »No, these people are just trying to intimidate us and discourage us from carrying on with our activities«. I was a part-time B.A. student at the university at that time, and one night in May—fortunately for me—I stayed the night in Lamontville where I was teaching. One of my colleagues told me, »Inkatha has attacked your house«. They had thrown petrol bombs at it and burned it down. The other two women had been in the house but managed to escape with their children—a baby and a five-year-old. I left the township after that because it was too dangerous for me to live there any longer.

We reported the destruction of our house to the police, but when they came, they only asked, »This has never happened in Umlazi before, so why did they come and attack you? Are you involved in politics?« There were some petrol bombs at our house that hadn't exploded and some bottles which we gave to the police for fingerprints. When we asked them later, »Where are the bottles for fingerprints?« they said, »We didn't need them so we've thrown them away«. This shows the attitude of the police when we report to them about Inkatha. I started to stay in a white suburb after that because I didn't know what would happen next in Umlazi. My kids are now staying with my mother, where they are safe.

Somebody phoned to tell us that there were rumors that Inkatha buses from KwaZulu were on their way to attack people in KwaMashu where Tozi's family, the Dlaminis, lived. Tozi is a close friend of mine as well as a teaching colleague and a member of NEUSA, so I phoned to tell her of these rumors. Tozi said, »But why would Inkatha attack us?« Since the Dlaminis didn't see any reason for an attack, they didn't run away. Very late that night the phone rang, and it was one of Tozi's sisters saying that Mr. Dlamini had been killed. Robert and another friend of ours in the house drove to KwaMashu to try to rescue them, not knowing whether the Amabuthos were still there. When we arrived, they had left and the casspirs were there. The Dlamini family was sitting outside with a neighbor waiting for the dawn. Next to them was some of their furniture and a bundle of things that hadn't been destroyed. Smoke was still coming from their house.

The Dlaminis had heard shots from the front door of their four-room house. There are still gunshot holes along the window sills and around the door. The Amabuthos are not very well trained, so they were just firing at random. There is a small bedroom at the back of the house, where the children stayed. Tozi was recovering from a caesarian delivery, and her two-week-old baby was with her. While some Amabuthos were shooting in the front of the house, others were trying to get in through a back window. Tozi doesn't know how she gained strength, but she took an umbrella and beat the men who were trying to enter through the window. She had pushed the wardrobe against the window and was beating them fiercely from behind it. Then a spear stabbed through her coming out just under her chin. It was very fortunate it didn't kill her.

One of the Amabuthos who had entered the bedroom said, »All the women must move out! Out!« He told the other Amabuthos that they must only fight with men. So the women managed to escape from the house, while Tozi's father and Thabo [Tozi's brother] remained inside. Thabo managed to escape because he is a fast thinker. The Amabuthos started to loot before they killed anyone, so Thabo joined them in looting as if he were one of them. Then he escaped. His father was an old man whom they shot and stabbed to death when he tried to run away. Then the Amabuthos attacked and burned the house. After hiding in people's toilets, the other members of the family returned to find Mr. Dlamini lying outside dead.

Inkatha attacks people suspected of being active in UDF. Tozi was in NEUSA, which is affiliated to UDF; Thabo was in the Youth Congress in KwaMashu; ancj their mother had resigned from Inkatha. Some time back in the mid-1970s, Mrs. Dlamini had been very active in Inkatha. At some stage she discovered that Gatsha was a liar. Her kids had also kept discouraging her from being involved in Inkatha activities. Inkatha might have had a grudge against her for resigning. They might have assumed that meant she had joined a UDF group. But Mr. Dlamini wasn't involved in any political group at all. He had never been arrested or anything. Most people who have been victims of Inkatha are not even activists in UDF, but if you are against Inkatha, they assume you must be UDF. If a boy is in the SRC [Student Representative Council] at school, they think he is UDF. This is why most people have been killed and most houses have been burnt by Inkatha.

During my friend Robert's interrogation when he was in detention, the Special Branch drew a diagram with the state on one side and the opposition on the other. Groups like ECC [End Conscription Campaign], NEUSA, and UDF were written in as members of the opposition. Robert deliberately mentioned Inkatha as opposing the state, and the Special Branch said, »No, no, no! Inkatha is on the government's side«. He was shocked that the Special Branch would actually say that. The Special Branch has also said to some people, »You must be happy to be in detention, because if we let you out, Inkatha would kill you«. Clearly, Inkatha and the government work hand in glove with each other. Each time the people take a stand against the government, Inkatha attacks them. For example, when NECC [National Education Crisis Committee] encouraged people not to buy books or pay school fees in 1985 because they pay taxes and there is a high rate of unemployment and the government should provide for education, Inkatha attacked people.

In March last year, the NECC had a national conference here in Durban. NECC announced that the government should respond to their demands within three months; otherwise, there would be another conference where people would decide what to do next. This conference had nothing to do with Inkatha, but Gatsha made a statement that it was being held in Durban to provoke him. Although it was in a white area, Inkatha attacked us. I ran for my life into a shop and asked the owner to close the shop, then peeped into the street through the glass door. The shop owner wanted to phone the police, but I told him, »The police aren't going to do anything against Inkatha«. Many people have been killed by Inkatha, but no arrests have been made. On this occasion the police came when Inkatha buses were arriving. After the war was over, they escorted them back into their buses.

Inkatha has killed hundreds of people. Last month nine school kids were killed in KwaMashu, and in Claremont, I can't say how many. In December, thirteen were killed in one family on one day. I am only talking about the very prominent incidents. In contrast, the UDF always avoids confronting Inkatha.

I am staying with Robert, who was detained last year. The police now realize that people use the white suburbs for hiding, so during the last state of emergency they concentrated their searches here. Each night we had to move to another house. When Robert was released from detention after about four weeks, he was shocked to find that I was still here to welcome him. He had been told in prison that I was a terrorist involved in the bombings that were exploding around Durban at that time. He had become convinced that I was using his house as an ANC base. The Special Branch had worked on his mind when he was in solitary confinement, and he had come to believe what they told him.

Being in hiding is very, very taxing. I become paranoid. I am suspicious of every car that stops and every telephone call. I can't even go to the shop. I actually detain myself. I can only move at night in disguise. I had to disguise myself yesterday to get my driver's license. I wore a domestic worker's uniform and a head scarf to the driving school. But it is still safer in a white area as far as Inkatha is concerned, and I prefer detention to being killed. Quite a few black people live in white areas or non-KwaZulu areas. Refugees used to live outside the country, but because of Inkatha, many people are now refugees from Inkatha inside the country.

The Consequences of Political Work

I'm not able to live with my kids because there is no place for us to stay together. They stay with me here at Robert's house over the holidays, but we receive telephone calls asking, »What are those black children doing here? Go back to the township«. When I returned from meetings, my kids would say, »Ma, this telephone caller phoned again«. It was very tough for them, but even so, they want to stay with me. But if I kept them here, who would look after them? I have to go to work and attend meetings, so it is much better that they stay with their granny, who is always at home.

There used to be phone calls even when the kids were not here. Anonymous callers would say things like, »Kaffirs should get out of that house«. Last December my kids were in the house when the Special Branch came through the window and raided us. That night there was a telephone caller who threatened, »Remember the necklaces and the hand grenades,« and then banged down the telephone. The three children were sleeping on mattresses on the floor when there was a bang, bang, bang on the window. I jumped up thinking, »Today is our last day«. I went to the other room where Thabo, Tozi's brother, sleeps and said, »The AWB [3] have come!« The police opened the window and entered the house. They looked around and wanted our identity papers. They didn't want to identify themselves, but we saw they were police because they had guns with them. They said they were going to take Thabo, but they left the house without him.

I think they raided us because Robert's house had become notorious by that time. I am not staying there right now because we were expecting raids there before the elections. I had planned to go back to the house today until I got the message that Robert was arrested at a demonstration this morning, so they might have a follow-up raid on the house while Robert is in prison.

I am now staying at another white man's house with a NEUSA friend, Vusi, whose life has also been threatened by Inkatha. He is also out of teaching now. An Australian guy who is staying there said that there was a street meeting of white people who were complaining about their black neighbors. Although this is defined as a white area by the Group Areas Act, there is a legal loophole according to which a black person can be here for ninety days. So the police have to prove that we have been here for more than ninety days, which is difficult.

Robert's big three-bedroom house has now become a home to me. One room is Robert's, another is mine, and there is a very big room that is used by other people who pop in and out. Tozi's brother started staying there continuously after his father was murdered by Inkatha last May [1986]. There is a difference between a home where I live and a place where I need to go when I am seriously hiding. I still use Robert's house as a hideout as far as Inkatha is concerned, but it is no longer a hideout as far as the state is concerned. I moved out during the state of emergency last year, but Robert stayed because he felt that he was not involved in anything serious. Then he was detained.

The Costs of Sexism

Women are doubly oppressed; we are oppressed by the regime and by our fellowmen. Even within the movement itself we have to fight against male domination. But it is different with NEUSA. I am the chairperson in Durban and the Soweto chairperson is also a woman who has been in that position since it started.

I became aware of sexism because of what I had to do as a wife. One time the classroom I was teaching in wasn't swept. The kids have to sweep the classroom themselves. I said, »Why is the classroom so dirty?« And the boys said, »It is these girls«. I used the whole period to deal with the issue of sexism, and the following day the boys jumped up to pick up papers to impress me. By the end of the year, their attitudes had changed. My experience of marriage was very useful to me in looking at men and relationships critically, and it strengthened me as well. I always draw a parallel between oppression by the regime and oppression by men. To me it is just the same. I always challenge men on why they react to oppression by the regime, but then they do exactly the same things to women that they criticize the regime for. I tell them that they are doing the job for the regime. The regime wants few people to be involved in the struggle so it will be ineffective, so the men are supporting the regime when they say, »You stay at home while I go out to meetings«. After the meetings they go back home and tell their wives about it. Often the man actually says at meetings what the wife was saying to him behind the scenes.

An Afrikaner Rebels

»I don't see myself as having any career in this country

other than working for the struggle... That's all I want

to do, and that's all that makes me happy.

I couldn't lead a life that is separate from it«.

HETTIE V.

...grew up in a typical Afrikaner home, joining the Voortrekker Youth Movement when she was a young child. This is an Afrikaner nationalist, Christian organization which tries to involve young people in cultural activities, including politics and religion, to try to keep Afrikaners on the right path and close to the Afrikaner nation. Most of the small minority of whites who oppose apartheid with any degree of conviction are English-speaking South Africans. Afrikaners who reject the government's conservative, racist policies usually become alienated and cut off from their own people, and thus have more to lose than English-speaking South Africans. Hettie V. has had the courage and motivation to risk such loss.

Thirty-one years old in 1987, and single, Hettie V. is a feminist who lives with a woman friend in one of the »gray« areas of Cape Town. She dropped out of university after only a few months to involve herself in political work more or less full-time, working in overcrowded, impoverished, and ruthlessly persecuted squatter communities. Often supporting herself by working at odd jobs, she finally landed a position as a journalist in 1983. She describes the dramatic political events she covered in this capacity—the 1985 march on Pollsmoor Prison to demand the release of Nelson Mandela, the police harassment of the black squatter camps on the outskirts of Cape Town — as well as the earlier upheavals and stay away of 1976. Active in the women's movement since 1977, she is an acute observer of black and white women's differing attitudes toward feminism. Fearless and committed, Hettie V. lives on the edge, politically and financially. Security is not what she wants, but excitement and meaningful action, and she forgoes white privilege whenever possible to contribute to the struggle.

Growing Up Afrikaner

I grew up in a small Afrikaans community within a larger English community where everyone knew everyone else. I come from quite a middle-class family, but my parents sent all of us children to a very working-class high school to develop a social conscience. The school had been set up for poor Afrikaners, so we were among the wealthiest people in the school, though we weren't that wealthy. It was a pretty conservative Nationalist Party-type of environment, though my family is relatively liberal on both my mother's and father's sides. But even as liberal Afrikaners they were Nats [members of the conservative Nationalist Party] and belonged to the Dutch Reformed Church because there wasn't anything else to be. Although they didn't step very far out of line, they had a more humanistic approach to people and weren't out-and-out racists.

I was one of four children and the only girl. I was always a very rebellious child and questioned things around me, even though it was often interpreted as »cheeky«. I would often stand up for other kids.

I was a member of the Voortrekker Youth Movement until I was about seventeen. We all learned to shoot guns at about ten years of age, and we used to go to camps where we'd participate in staged battles. Some of us would stand guard against the »terrorists« who would attack the camp in the middle of the night. I wasn't a willing or good Voortrekker. In fact, I was quite a rebel within the movement.

We were being prepared to deal with the »black onslaught« [the expectation of being attacked by black people], and we used 22 guns which were loaded with real bullets. We learned about politics, basic survival, how to operate a two-way radio, how to do first aid. It was designed to fit us all into the civil defense system. In general, children learn to shoot in Afrikaans schools from the age of about twelve. It is part of the school cadet system for men, and the Youth Preparedness Program teaches both girls and boys to shoot. In 1976 [the year of the Soweto uprising], the school cadets patroled our school with guns from the school armory. People stood guard at night and over weekends in anticipation that the school would be attacked, though this never happened.

I didn't mind being a Young Voortrekker because I thought it was useful to learn to shoot. Afrikaners are not like English people, who don't like to argue and to get emotional. We talk and argue about religion and politics all the time. Those are our favorite subjects. All my uncles are in the Broederbond [a secret society of Afrikaners dedicated to furthering the interests of their people], and we often went on holidays where a couple of dozen people in my extended family would sit and argue all night. They still liked me because I'm one of them, even though I didn't agree with them. Afrikaners are very political people. You'll never find an Afrikaner who is undecided about anything.

I also had endless arguments with people in the Young Voortrekkers, and I eventually resigned on a point of principle. We'd get these badges like the Boy Scouts do, and one of the tests for the last badge remaining for me to get was to prove that I had a sound understanding of the political situation in South Africa. The person who tested us was the Nationalist Party's secretary for the town I grew up in. I had a blazing argument with him, and he failed me, which finally gave me a good enough reason to resign.

I became politically conscious in primary school at about ten or eleven years of age. But a lot of it was just rebelliousness. I remember during the Six Day War between Israel and Egypt, I was the only person in primary school who supported Egypt. I did so because everyone else supported Israel. I always identified with the rebels. My parents were very freaked out about me because I had pictures of Yasir Arafat and Fidel Castro on my wall when I was a child. A lot of this was just to be provocative. But it became more than that when I was about twelve. Because the school was not an academically prestigious place, the teachers were people who cared, and they encouraged us to have debates about politics. I was anti-apartheid then, which wasn't a popular position in the school at all, and my brothers followed suit. We were known as the commies, the reds. When people didn't want to write a math test, they would start an argument with the teacher about communism, and they knew that we'd take up the whole period arguing with him, so they would get out of their test.

Two of my brothers and another friend were also very politically active at school. When I was in standard eight, one of us was in each of the high school classes. We took over certain organizations like the debating society and the school magazine, and we went to things like the Nationalist Party Leadership Training Conferences for high school students and tried to subvert them. We also organized a strike at our school. The girls still had to wear hats at that time, and we decided that this was nonsense, so we got everyone to throw their hats in the dustbins. We didn't have to wear hats any more after that.

I really don't understand why I grew up as I did. The only explanation I can think of is that my parents were more left than their parents, and we were more left than them, and that it may have been a kind of generational progression. Also, the kind of attitudes that they taught us toward people forced us to look at things in a more critical way and to question things. Basically, my parents are very kind, even though they're probably racists. They would never consciously undermine another human being's dignity. If a beggar or a drunk came to the door to ask for money, they treated that person with respect.

I had a very unsexist upbringing. We always did the same chores at home and had the same rights. I got the same toys. My parents encouraged me to stand on my own feet. They told me that they realized that I was going to be an independent type, so I should know how to look after myself. I was confronted with a sexist world when I went to school, so I naturally rebelled against that, too. I was also very involved in sports like rugby and cricket. I was called a tomboy, but there wasn't a stigma against this in the community I grew up in. It was only when I hit puberty that I was supposed to change.

Working in Squatter Communities

I always wanted to be part of an anti-apartheid group, so that's why I went to an English-speaking university. There were no anti-apartheid groups at Stellenbosch [an Afrikaans university]. My parents really wanted me and my brothers to attend an Afrikaans university. They feared if we went to UCT [University of Cape Town], we would become involved in politics. However, we eventually did go to English-speaking universities and did become involved in student politics. But I left university after six months because I quickly became very disillusioned with it.

While I was still at UCT, I started working in squatter camps around Cape Town, and I worked there full-time after I quit university. A lot of my friends supported me financially while I did this work, but I also started a scrap recycling project with a few other people. There was a big rubbish dump just outside Cape Town where we collected glass, bottles, cardboard, and metal, to sell. And we cut firewood, which we also sold. I didn't really worry much about money.

These squatter communities had absolutely no access to resources like sewage systems or water. The people there wanted projects that would strengthen the organizations and politicize people, so together with others I did literacy teaching in a consciousness-raising way using the methods of Paulo Friere [a Brazilian theorist and radical activist who devoted his life to trying to advance the fortunes of impoverished peoples]. We also tried to train barefoot lawyers and barefoot doctors in the community and helped to get vegetable gardens going.

A lot of the squatters where I was working were Coloured people who had been moved out of white areas. Insufficient housing had been provided for them in the areas where they were supposed to go, or they were too far from their places of work, so they had no choice but to squat. At that stage there was a three hundred thousand housing shortage in Cape Town for Coloured people. In those days most squatters had corrugated-iron shacks, whereas today far more of them have plastic and cardboard shacks, which are much worse. A lot of them were quite settled communities that had sometimes been there for years. They were relatively secure on the land because most of the squatting laws hadn't been passed yet. But they were still very poor, very unorganized, and very crime-ridden. Especially in the Coloured areas, there are lots of gangs, and they are also very vulnerable to gangs from other areas.

I remember speaking to one woman in a very small squatter camp who had been raped fourteen times by gangs who came in a truck on weekends. These gangs would go through the community, bash down all the doors, take everything, rape a few women, then leave in their truck. A committee tried to organize a system where someone would blow a whistle as soon as the gangs came, to rally other people for help. But people ran away into the bush when they heard the whistle. Because this woman's house was the first one, she got hit every time. She reported what happened to the Divisional Council which was in charge of the land, and she and others asked to move their shacks closer to a big community to get some protection. But the Divisional Council said, »No. Once you've built a shack, you're lucky if you're allowed to stay. You can move to a proper housing area, but you can't move around here and make it easier for yourself«.

People wouldn't try to lay charges against the gangs for the rape for fear of being killed in retaliation. Gangs are one of the reasons why the Coloured areas aren't as politically organized as the African areas. Someone said that about eighty percent of Coloured boys belong to gangs. Some of the gang members make their living by being drug dealers, but most just engage in petty crime or violence in their own communities. And the police have never tried very hard to get rid of them or to control them because they keep people scared and inside their houses rather than going to meetings and getting involved in the community. The gangs have got a hell of a lot of power and quite a lot of wealth in some areas. Some community organizations are trying to work with them to change their attitudes.

The community leaders and committees in the Coloured areas were almost all female. Women are exceedingly strong in the Coloured community because traditionally they work. The major industries in Cape Town are garment and textile production and food and canning, both of which employ many Coloured women. So Coloured women are often quite stable wage earners, whereas Coloured men often work in more unstable and seasonal jobs like fishing, farm labor, and construction. Coloured women have traditionally worked, brought up the children, kept the house; in squatter camps, they have often also built the house, worked in the community, sat on the committees, been active in churches, and slaved their guts out to get their children educated. A lot of them are fierce, strong women.

Police Brutality and Political Resistance in 1976

Nineteen seventy-six was a very dramatic time. The unrest in Soweto spread to Cape Town, and there was a hell of a lot of action here. The squatter camp I worked at most of the time was close to a lot of it. The repression got much worse around that time. Our tires were slashed outside our homes or outside the squatter camps all the time. We were always being stopped by the police and searched and had to find back ways to go into the camps. A lot of the roads were closed because the cops set up roadblocks. Sometimes I got through by telling lies to the police if they didn't know me. I'd tell them that I was from Stellenbosch University and that I was teaching Bible classes to squatters. I told them I wasn't scared to go in because God was on my side and this kind of work had to continue, especially at this time. Sometimes they'd even give me an escort.

After June 1976, the police told everyone who attended our literacy groups that they would lose their houses if they continued to come. Most of the people didn't come back so we had to change our strategy, which was actually very good. We trained the people who were already a bit educated, and who were in leadership positions, to teach the classes themselves. So the work became less visible, and it didn't create dependency relationships. White people going into communities was always a very suspicious thing to the cops. They knew that we discussed politics because there were police informers in our groups.

In 1976, there were school boycotts, fighting in the streets, barricades. A lot of people were shot. For three days there were riots in Adderley Street [the main road in Cape Town]. A stayaway had been called, and black people decided to go to [largely white] Cape Town because white people had been so isolated from the unrest that they didn't have a clue what was going on.

The stayaway started with a march by a group of Coloured school kids who had taken a train into Cape Town. People from all over joined them, and within half an hour there must have been ten thousand people walking up and down Adderley Street. After a while all the shopkeepers closed their doors and put down their burglar bars. The cops were armed with guns and teargas and truncheons—wooden batons with lead in the middle. They formed two lines on either side of Adderley Street, then marched toward each other so that all the people were squashed up the side roads. Then they shot teargas and clobbered people with their truncheons.

I got clobbered over the head by a cop who had probably been watching me. I wasn't doing anything, but I was with black people so I obviously wasn't a shopper. I thought I had been shot because the cops had started shooting over the heads of the crowd. I was unconscious for about ten minutes. I woke up with everyone running over me, and feeling a pain in my head. I thought, »I have a bullet in my head. I'd better not move because then I'll die«. I was paralyzed for a few minutes. People carried me into a shop, and a guy said, »No, you weren't shot. You were just clobbered. I saw the policeman do it«. Then somebody else looked at my head and said, »No, there's a bullet in your head,« and I promptly became paralyzed again. The blow had cracked my head a bit, and I still have a dent in my skull from it. But I'm never scared in these situations. When there's shooting, I just hit the ground. I'm always a bit terrified afterward, when I realize what has happened.

The next day I went back to Cape Town—but with a crash helmet! As soon as a group gathered, the cops would disperse them with tear gas and baton charges. Eventually there were about a hundred people in front of the city hall on one side and the cops on the other side in two vans. Two black guys were walking between the two groups when the cops ran across, grabbed them, and started dragging them to their vans for no apparent reason. About a hundred of us surged forward to go to rescue these two people when the cops pulled out their handguns and shot at us. Two people were killed. Then thirty police vehicles arrived, and the police started charging us. A group of us ran into the city hall followed by about a hundred policemen. Eventually they arrested and beat so many people that the demonstrations stopped. This kind of crisis went on until the end of 1976. They didn't call a state of emergency, but they killed and injured many people. All the people killed were black.

The police did all kinds of other ugly things during that period. For example, they announced that they had found pamphlets that called for a »Kill-a-White Day«. Every black person was meant to kill a white on a particular day. We knew the pamphlets were coming from the cops to increase white paranoia so as to detract from the real issues and turn the unrest into a racial war. On the »Kill-a-White Day« a lot of white people didn't move out of their houses. They had their overnight bags packed and their guns ready. But not a single white person was injured in the whole country in spite of the wide distribution of these pamphlets. This shows how much maturity there is in the black community despite months of harassment. People knew that the call wasn't coming from their people, or even if it was, that it was something that should be ignored.

Feminism, the Left, and Anti-Apartheid Politics

I joined the women's movement at the end of 1977. It was very small at that stage and not very active. It had started in 1975 when Juliet Mitchell [British feminist author] came out from England to give a lecture here. We confronted white left-wing organizations a lot with their sexism. We organized a walkout of a National Union of South African Students' conference in 1978 by about sixty percent of the women on the grounds that they didn't take women's issues seriously, that they saw us as peripheral to the struggle, that the leadership positions in NUSAS were very male-dominated, and that we didn't agree with the hierarchical nature of the leadership positions. It caused an incredible trauma and took about two years before the women got properly integrated into the left again. We were accused of dividing the left. Despite this, feminism was at the height of its popularity on campuses in 1978-79. The women's movement was much noisier then than it is now, but there are probably more feminists around today. Feminism is now more accepted by the left because of the kind of noise we made then.

But in those days the women's movement was a very white, middle-class thing. Feminism didn't take off at black universities. In fact, there were no active black women's organizations, other than church ones, and there were no nonracial political organizations like UDF. So whites basically worked on campus, and feminists worked in organizations like Rape Crisis. A lot of the criticisms of us—like that we were too Western — were valid because we took feminism straight from America and Europe and fought for the same things here. Nevertheless, we felt that the issues we focused on had to be taken up, and that we weren't just being divisive.

When black women formed women's organizations, they chose to get involved in more grassroots community issues like rent, housing, and food. With the birth of nonracial organizations, most feminists chose to get involved in anti-apartheid organizations rather than to remain an outside pressure group and be branded as lunatics. They worked within these organizations to push for equality of women within the struggle and for other women's issues like child care. Issues like contraception or women's right to determine their own reproduction are more problematic. Although thousands of women have back-street abortions, there's no way that abortion will be taken up as an issue. [Abortion is still illegal in South Africa.] In the black community, people are relatively conservative about things like this and quite religious. This makes it a difficult issue for white women to take up because if we do, it becomes a case of cultural domination. And contraception is a very dicey issue in South Africa because family planning is used by the state against black people in such a racist way.

I don't think the struggle will ever stop for feminists. The conclusion I came to last year, which is quite a drastic one because I see myself as a revolutionary, is that feminism will always be a reformist struggle in this country. Whoever is in power, we will still have to chip away at things. There will never be a mass-based feminist movement that will threaten or challenge the system, whoever is running it. So we have to adapt our strategies accordingly.

Feminists in this country have to commit ourselves very firmly to the struggle in general if we want to have any effect afterwards; otherwise, we're just going to be seen as fence sitters. It's not a question of being manipulative and saying, »O.K., we'll adopt these strategies because that way we'll achieve our hidden agendas«. It's recognizing that housing and schooling and torture may not be »feminist« issues, but that they are important issues. And as feminists, we cannot ignore the important human issues. Our position is very difficult, because a lot of people who are very strong feminists are also white and middle-class. That means that we have to triply earn our credibility, and we're viewed with triple suspicion.

Working as a Journalist: 1983-86

About four years ago, I became a freelance journalist. I covered politics, labor, education, housing, and a little bit of central government stuff. And I did a lot of features on community issues like removals and demolitions in squatter camps that were very horrifying.

Whites weren't allowed into the black townships in those days, so I often had to be smuggled in. I would put on a balaclava and a blanket, and then the taller people would walk in a group around me so that I wasn't obviously a white person going in there. Had the cops caught me, they would have taken my tapes and thrown me out and they also might have arrested me.

For example, in 1983 a new squatter camp called KTC was started with twenty houses made of sticks covered with black plastic rubbish bags. Because of demolitions in other squatter camps, KTC kept growing. But every day the cops and the administration board would demolish and burn people's shelters. It became a big issue in the community, and some people who had houses elsewhere put up shelters there out of defiance. Within two or three weeks there were ten thousand people living there, most of them women. And it was the women who organized the resistance. A lot of them had come to Cape Town to join their husbands, who had been living in the [so-called] single men's hostels as migrant workers. Other women from Cape Town joined them.

Although it was winter, the cops' raids got bigger and bigger. Sometimes it would be raining, but the cops would still come and bash down the houses, and whole families with kids would have to sit there in the rain all day until it was dark enough to build their shelters again. Eventually people started breaking down their shelters early in the morning and burying their materials so that they wouldn't lose everything when the raids came, because it was impossible to get any sticks or rubbish bags anywhere any more. A lot of people dug holes in the ground and put plastic over the top because they said the police couldn't demolish holes. It was a nauseating business. People would have prayer meetings and sing and watch the cops demolishing their shelters and the cops would then shoot tear gas to get them to move away from the scene. This went on for about four months. One day hundreds of cops came in and demolished the shacks, then put barbed wire around the place, parked a few casspirs there, put search lights up, and stayed there for weeks and weeks so people couldn't rebuild at night. So most of the people moved to Crossroads [the most famous squatter township in South Africa] and the demolitions then started there.

I also covered all the school and university unrest in 1985 until the state of emergency was called in October 1985.[4] It was a very dramatic period for journalists because people were being shot every day or two.

The unrest [in the western Cape] started in August 1985 with the march on Pollsmoor to deliver a message of support to Nelson Mandela who was imprisoned there. The march was meant to start at Athlone Stadium, so I went there at five o'clock in the morning, but the whole of Athlone had been cordoned off with armored vehicles making it impossible to get through to the stadium. There were alternative plans, but no one knew what they were. Some people went to Athlone, but the cops whipped them and forced them away. One segment of the march started with about four thousand people from Hewat, a Coloured teachers' training college. The cops whipped them and trapped a lot of them in a hall, then threw tear gas into the hall causing a big commotion. About a thousand more people marched from UCT. Eventually the planning committee for the march started marching from just outside Pollsmoor, and they were all arrested. After that, all hell broke loose everywhere.

The police became very paranoid about the kind of press coverage they were getting, especially from the journalists with foreign connections. They started shooting at journalists with tear gas cannisters or rubber bullets. Rubber bullets are four inches long and about one inch wide and made of very hard rubber. The police call them rubber batons. They are cylindrical in shape so they've got sharp edges. If they are shot in the air and then drop down on someone, they're not lethal. But if they are shot at someone at close range, they're as lethal as anything. People have been killed by them, especially when they get hit in the throat or in the eye. And I've seen people with furrows cut through their skulls from being hit at too close range with them. Instead of shooting them in the air, the cops shot them right at us.

I was hit by a rubber bullet once on my hip, but it wasn't serious. I had a huge bruise and a mark from it which took months and months to go away. The cops were shooting tear gas at the students at the University of the Western Cape because they were stoning a bus, and I got caught in the middle. Suddenly there were stones raining down on me, so I jumped into a ditch. I was hit by a rubber bullet just as I was jumping. I thought, »Oh, shit, I've been hit!« but I had to get out of there in a hurry because the cops stormed onto the campus and started arresting people and shooting real bullets at them. So I ran with some people and hid in a lab. I put on a white coat that I found lying around, then walked out as if I was a member of the university staff. A group of students recognized me and called me because someone had been shot in the head and they wanted a journalist to take pictures of this. Then we organized one of the caretakers to try to get the victim to a hospital in the maintenance van without being arrested. By that time I'd forgotten that I'd been hit.

It felt a bit like being a war correspondent where, although you're on the sidelines, you're actually on one side. And the cops knew it. You can't maintain a position of neutrality in such a situation. The whole concept of journalist-as-observer disappeared when cops started targeting us. I became totally dependent for protection on the people who could hide me or carry my tapes out. If the cops came toward me, I'd pass all my tapes and my film to anyone and say, »Please keep it«. And to get my stuff back, I'd give them my phone number and hope for the best.

I've often been tear - gassed, which is the most awful feeling. The police don't use a tear gas that makes you cry, like in the States. It's something that attacks your nerve endings wherever you're wet on your body, like in your mouth, your eyes and throat, your lungs, under your armpits. It gives you a sharp unbearable pain, so you stop breathing. If you put water on your skin, which a lot of people do because that used to help with the old kind of tear gas, your whole face feels as if it's on fire. There's another kind of tear gas they use less often that makes you vomit.

We've discovered all kinds of remedies for tear gas. I always used to walk around with a lemon, because it helps if you put lemon on a piece of cloth and breathe through it. Without lemon, it becomes so painful that you don't want to breathe, and you can't see where you are going because your eyes are aching so much. It's a very effective crowd dis-perser. As long as it's around, you're almost totally immobilized, and you feel sore for hours afterward. If somebody comes close to you and smells it on your clothes, they'll feel sore as well. People have died of suffocation from it, especially when they're in confined spaces. I'm far more scared of tear gas than of anything else, because with rubber bullets you still have a chance to see if someone is pointing a gun at you, or you can hit the ground, or they may miss. I understand why tear gas causes people to panic completely.

I've seen people who've had six-month-old scars from being hit with sjamboks. They cut the skin and leave huge weals. One of the cops' favorite things is to hit women across their breasts with them. When they disperse gatherings, they're meant to only use as much violent force as is necessary, but they'll often hit people until they fall to the ground, then carry on beating them which, of course, prevents them from dispersing. They like doing that to journalists because they hate us. I've covered a lot of white student protests and seen people getting completely freaked out from being sjamboked. This is a very normal reaction in one sense—in that it's a very invasive, abusive, and violent experience, and some students complain of nightmares afterward. But people in the townships [black people] experience it all the time and don't make such a big deal of it.

People didn't understand the concept of a progressive journalist in those days, so the press was seen as part of the system during the first few weeks of unrest. We were in the crossfire a lot, and it became very dangerous. Journalists had their cars stoned and petrol bombs thrown into them, and they were always being stopped at roadblocks—people's roadblocks, not police roadblocks. It took about a month before people realized that some journalists served a useful purpose, and then they started being more protective toward us. Usually what happens is that the people are on one side, in a school yard or at a university or in the street, and the cops are on the other side, and the journalists stand in the middle somewhere, but slightly to the side. We'd go and interview the people, and if we had the guts, we'd go and interview the cops, but we didn't want to be seen talking to the cops. Then somebody would throw a stone or somebody would shoot, and it was like watching a war being played out in front of you.

There had been school boycotts since June of 1985 which all the Coloured and African schools participated in. Every day something awful happened at some school, like the school kids would be having a meeting or a demonstration in the school yard, and the cops would come and shoot lots of people, and some would be killed. The cops were trying to force people to stay in classrooms, so they'd be posted outside the classroom doors or in the classrooms to see that the teachers were teaching. Eventually the government closed down all the African and Coloured schools in Cape Town. They said, »If you want to boycott the schools, we'll close them down«. People then decided to reopen the schools because they wanted them to be changed, not shut down. So on 17 October 1985, parents, teachers, and children planned to reopen the schools everywhere.

One of my most terrible experiences occurred at a school called Alexander Sinten in Athlone. I went to the Athlone area [a Coloured suburb of Cape Town], because I thought there would be the most trouble there. There were a couple of kids standing around singing in the quad when I walked in, and parents and children were arriving to open the school [Alexander Sin ten]. I went to interview the headmaster, who was standing at the gate when two vans and about six cops arrived and arrested us. They arrested me for trespassing on government property. Then they put guards at the entrances to the quad and said that all the children were under arrest. Next they called for reinforcements to come and take about one hundred seventy of us away. Meanwhile, more and more people kept arriving to reopen the school. There are three other schools in the area and a teacher's training college, and lots of people came to see what was going on. Although the cops had closed the gates almost immediately, about four thousand people gathered outside. By this time I was under arrest in the back of a police van with a lot of other people.

The people outside the gates took all the cars that were parked on the pavements, picked them up, and stuck them in the middle of the road so that the casspirs couldn't come in to take the rest of us away, and they got the local butcher to park all his refrigeration trucks in the road. After about forty minutes the place had been cordoned off by the people and was absolutely impassable to traffic. I was still sitting, as hot as hell, in the back of a van with the teachers and headmaster and some of the students. By this time the cops were absolutely panicking because it was only three days after a cop had been killed by a Muslim crowd at a funeral in Salt River [a neighborhood nearby]. Cops don't often get killed in South Africa, and there were a lot of Muslims outside the school shouting for holy war. The cops were standing right next to our van, not knowing what to do.

An imam [Muslim priest] came to try to negotiate for our release. He said that the people would stop the blockade if those of us inside the gates were let out, but the cops said, »No, we're never going to get out of here alive unless we have these people in the back of our vans«. And it was true. By this time the stones were raining down on that place, and we were kept there for four hours. They wouldn't even let us go and wee or get water or anything. Then a huge army truck that's used for towing broken-down casspirs and other large vehicles drove over the back fence of the school, flattened it, and brought in a lot of troops and riot weapons, because up to that point the cops only had guns.

We shouted from the vans to try to warn people that these guys were coming in from the back. Then they started firing tear gas at the crowd to try to clear them away. I stopped counting after about fifty-six canisters, but the people just picked them up and threw them back. All the cops had on gas masks, but we had to sit in an open police van in an absolute cloud of tear gas. We thought we were going to die. Cops then charged from all sides, and the people moved a few blocks back. The breakdown trucks came and towed all the cars off the road, enabling the cops to drive off with us in the backs of the vans. They also brought in more vans, loaded about half the people into them, and charged out of there. Somebody threw a stone at the guy who was driving our van, while everyone shouted, »AmandM,« and he pulled out his gun and started shooting.

We spent the rest of the day in jail, until the lawyers came and got us out because they'd arrested us for nothing. I was the only white person there, but it took them a while to figure out that I was white because a lot of Muslim people are lighter than I am. They put all the women, girls, boys, and men in separate cells. In the women's cell there were twenty-three of us, two teachers, myself, and the rest were mothers who had come to support their children. They were people who hadn't been in prison before, and they became more and more defiant as the time passed. A cop came in to find out if anyone had any medical problems, and one woman said she wanted pads. He said, »O.K., I'll see what I can do«. Then another woman said, »I want maternity pads,« and somebody else said, »I want Liletts [a kind of tampon]«. They went through all the brand names for sanitary napkins, which made him very embarrassed. He was blushing when he said, »I'll bring toilet paper and that will handle it all«. That sort of incident cheered everyone up.

One woman said, »I don't know what's going to happen to my house because my children are also here today«. Another said, »Well, my husband is here, too, so I don't know what's going to happen when my primary-school children get home«. They'd compare notes as to how many of them were united in this thing. It was very sweet. But eventually the cops put me in a separate cell because they realized I was white.

I have been in police cells a number of times for being in the wrong township at the wrong time, but I've never been in serious trouble. The longest time I've been in is overnight. The cops would tell a crowd to disperse but I'd want to be where the action was to record it. I'd often end up being the last one to get away, and that's how I got hit a few times.

After the 1985 state of emergency was declared, journalists were suddenly much more restricted. We couldn't report on police action. We weren't allowed to take sound recordings or film recordings any more. Restrictions became even worse after the state of emergency was renewed on 12 June 1986. We weren't allowed to be at the scene of unrest.

There were very heavy penalties for breaking this and other rules — like ten years in prison or a fine of twenty thousand rand [$10,000] or both. After that, the restrictions kept getting worse and worse. Basically we could only cover the police's side of things. Then they centralized it all, so that we couldn't even interview local police any more, and we had to get the information from Pretoria. So I quit being a journalist.

On Being White in the Anti-Apartheid Movement

Before 1976, whites were involved peripherally in the labor movement and in work like I was doing in the squatter camps. After 1976, there was a huge Black Consciousness movement, and whites were not part of the mainstream anti-apartheid movement. After 1980, the nonracial democratic organizations were being born all over the place, and the nonracial organizations like the UDF became the strongest. I've never experienced animosity from anyone in any of these organizations on a racial basis, which surprises me.

It also surprises me that I could go into a riot in a squatter camp without anybody threatening me or being hostile toward me. I don't understand it. I think that there is something very, very special about black people in this country. People are prepared to listen to me and to judge me as a human being and not merely as someone with a white skin. It amazes me every time I experience it because I don't think that I would have that tolerance if I were in that position. And I don't think white people in general would put up with so much and then still be open to people as human beings.

I don't have any doubts that there will be a place for progressive white people in this country in the future. I think the paranoia common among white people is very unfounded. I have always organized my life so that I could focus on my political work. That's all I want to do, and that's all that makes me happy.

Marriage Across the Color Bar

»I don't just believe that the personal is political,

as most radical feminists do, but that the political

is also often very personal, as my story of

>love across the color bar< shows«.

RHODA BERTELSMANN-KADALIE

...was born in 1953 in District Six, the low-income black community that was completely destroyed by the government's efforts to separate black and white residential areas described by Rozena Maart in chapter 19. »Because of the Group Areas Act, we had to move around Cape Town quite a lot«, explained Bertelsmann-Kadalie, a Coloured woman, thirty-four years old in 1987 when I interviewed her.

After graduating in 1975 from the University of the Western Cape,[5] a black university, Bertelsmann-Kadalie completed an honors degree in social anthropology there, then went to the University of Cape Town to study for an M.A., also in anthropology. She didn't complete this degree, but in 1986 obtained an M.A. in women and development studies at the Institute for Social Studies in the Hague, the Netherlands. Bertelsmann-Kadalie was on maternity leave from teaching at UWC at the time I interviewed her, nursing and caring for her few-months-old baby, Julia.

Although Bertelsmann-Kadalie didn't tell me that her grandfather, Clements Kadalie, had been a famous organizer of workers in the 1920s, other people did. Perhaps pride in her family name, as well as her feminism, accounts for her desire to maintain her father's name. But she also wanted to take the last name of her white husband, Richie Bertelsmann, to emphasize to the South African authorities that she was married to him, despite the illegality of this union in their eyes. There are many different ways to rebel against apartheid, including ignoring the racist laws against interracial marriage, as Rhoda Bertelsmann-Kadalie did. Most of her story is taken up with the police harassment she and her husband experienced owing both to their marriage and to their political activities.

Growing Up Coloured

I come from a big family with nine children. I was aware of apartheid from a very young age. When I was six years old, we moved to a white area in Cape Town because my father was transferred there. He was in charge of the municipal laundries where white people used to come and bring their washing. We were the only so-called Coloured family living in the area. So from my second year of school onward, I was living in a white area while always being made aware that I was Coloured. For example, I used to play with a white minister's daughter in the neighborhood. Her mother used to say to her, »You can only play with Rhoda for five minutes because she's black«. After school I used to meet a white girl called Paddy to play with her before we went home. One day I walked her home and at the door said, »Bye-bye, Paddy«. Her mother said sternly, »Miss Paddy to you«. I said, »But she doesn't call me Miss Rhoda«. »She's saying that to you because you're black«, my mother explained. And one day I was suddenly told, »You can't play here any longer because it's a park for white people«. I registered these experiences as a little girl, though I couldn't make sense of them.

My father became a minister, and when he complained about the apartheid in the churches, another minister—whom he thought was a friend—said, »You sound like a communist«. I had a lot of white Christian friends who would be friendly with me in the church but wouldn't look at me in the local supermarket. I used to run interracial camps. Many of my white friends used to invite me to their parties, and they would say, »Oh, meet my nice friend who's not at all bitter«. I would be asked to address white schools on my experiences as a Coloured student, and when I began to show my indignation and anger about the way I was treated, I wasn't asked as much any more. My younger sister and I have been thrown out of restaurants because they were for whites only or because we went in the whites-only entrance.

Marriage and Police Harassment

I met Richie at the University of the Western Cape when he joined the staff as a new lecturer there in 1980.[6] A colleague of mine was already acquainted with him, and the three of us went to see a very poignant play on migrant labor and the difficulties it creates for family life. I was very impressed by what he thought about the play, though I also felt that he was trying to impress me politically. He kept saying to me, »Well, don't you think I also feel disgusted about the situation in this country?« We dated each other every week from then on.

At that time I was the youth leader of our church in a Coloured township where the crime rate was very high. Richie isn't particularly religious, but he went to our church with me, and he was very impressed by our efforts to provide recreation and political outlets for the people. He loved doing that kind of thing with me. It was the first time in his life that he was involved in a Coloured township activity, because he had grown up in Pretoria and had attended very middle-class white schools. After courting for two years, we realized our relationship was becoming serious. I had wanted to break it off several times because my father was opposed to it because Richie isn't a Christian, and I felt I couldn't cope with my father's pressure. While Richie's father opposed our relationship on racial grounds, his parents were also apprehensive about the problems which we as a »mixed couple« could encounter in a society like ours. When we decided we wanted to marry, they realized there was nothing they could do about it so they might as well accept it.

It was still illegal for people of different races to marry then. We decided to stay because we felt that too many people in our situation had left the country and not opposed that law. We thought the best strategy would be to buy a house, so we looked for one before we even told anybody we were getting married. As university employees we qualified for a subsidy, so it was quite easy to get a house. We bought one in Observatory — a white working-class area [in Cape Town]—because it is more tolerant than most. Communes in which white students live with their black student friends are flourishing here. We bought the house under Richie's name because only he qualifies for a house in this legally-defined white area.

Marriage was the next step. We decided to fly to Namibia [7] over a weekend, marry, then come hack, and move into our house. So in December 1982 that's what we did. The Mixed Marriages Act had been repealed in Namibia in 1978, but that didn't mean that the people there liked marrying us. The white magistrate didn't even look at us, and during the marriage ceremony he asked: »Do you, Richard Bertelsmann, white man, marry Rhoda Kadalie, Coloured girl?« He tried to rub it under our noses that we were breaking the law in South Africa and that he hated having to marry us. I wanted to keep my maiden surname for feminist reasons. But for political reasons I decided to adopt Richie's name to rub it under their noses that, »I am married, and you will have to accept it whether you like it or not«.